(1).jpg)

BETWEEN FIRE AND WATER: IZMIR IS BURNING

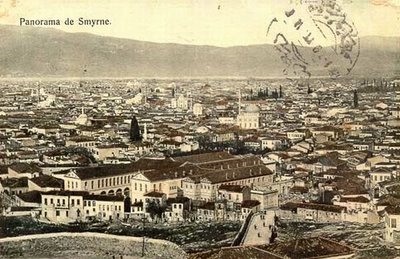

After the Battle of Dumlupınar, the Greek army collapsed and began to retreat. On Saturday, September 9, 1922, Izmir fell. Ottoman soldiers entered the city. The exhausted Greek soldiers were leaving the city by ships. The quay was in utter chaos. Local Greeks, anxious about their fate, were trying to board ships. Greek refugees from Aegean villages had also filled the quay. On the morning of September 9, the number of refugees reached 150,000. There were about 50,000 soldiers as well. The city's Armenians had taken refuge in the bishopric. Only the Levantines in the city—that is, local English, Americans, French, and Italians who had lived here for over a hundred years—trusted in the help of their consuls and believed that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s soldiers would treat them well.

Why Did He Even Want to Take Izmir?

Mustafa Kemal and his companions, who were waiting in the town of Nif (now Kemalpaşa), 50 km from the city, entered Izmir on Sunday morning, September 10, in five brand-new cars decorated with olive branches. His first act was to appoint Sakallı Nureddin Pasha as the governor of the city. Nureddin Pasha gave assurances to the public, saying everyone should return to their work.

The next day, Kemal Pasha came to lunch at Kramer Palas on the Kordon. At first, no one recognized him. Once the identity of the guest was explained, service began immediately. It is famous that the Pasha asked the staff, “Did King Constantine of Greece come here and drink rakı (an alcoholic beverage)?” and when told that the King had never set foot there, he said, “Then why did he even want to take Izmir?”

That same day, gangs in the city began harassing Armenians, looting their homes and shops. The streets were filled with corpses. The sound of machine guns never ceased. Greek soldiers who couldn’t escape surrendered. Meanwhile, M. Kemal Pasha sent a telegram to the League of Nations stating that “due to the excited mental state of the Turkish population, the Ankara government cannot be held responsible for the massacres.”

The victors believed that the time had come to take revenge for the oppression they had endured from Christians over the past ten years. Metropolitan Chrysostomos, who had supported the Greek occupation and did not leave the city, was handed over to Nureddin Pasha. The Pasha had him lynched by the crowd in Konak Square. Admiral Bristol, the American high commissioner known as a friend of the Turks, gave orders to his troops not to assist the Greeks and Armenians in the city. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of refugees were still waiting under horrific conditions on the quay, guarded by Allied soldiers.

Infidel Izmir Becomes National

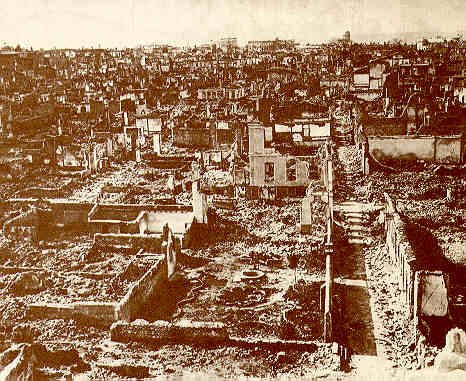

On the morning of Tuesday, September 12, flames rose to the skies from the Armenian quarter. By evening, a second fire engulfed the Greek quarter. The next day, the fire reached the Kordon. Ammunition and petroleum buildings in the city were exploding one by one. The sky was blood-red. The smell of burning filled the air. People caught in the flames rushed to the quay. When the cool aegean summer sea-breeze was replaced by a southeasterly wind, the fire shifted westward.

As the fire approached the mansion in Bornova where M. Kemal was staying, the Pasha immediately traveled by car through the panicked crowds fleeing the fire and relocated to the mansion of his future father-in-law Muammer Bey in Göztepe. The fire was only extinguished on September 18.

On September 23, a new fire broke out behind the Hisar Mosque. Except for Kadifekale and its slopes—where most of the Turks lived—the Jewish quarter, the Punta station, and the Standard Oil Refinery, the entirety of Izmir was burned down. In an area of 2.6 million square meters, 25,000 buildings were destroyed. The movable property left behind by those who fled was worth 3.5 million gold coins. Insurance companies refused to pay for the damages, citing that the fire occurred during wartime.

Meanwhile, as control over the gangs was completely lost and the Levantine areas of Bornova and Şirinyer were also set ablaze, the Allies began evacuating their citizens. However, there were not enough means of transport for the Greeks and Armenians. People were caught between water and fire. Some jumped into the sea, and many drowned before they could board any vessel. Ships were transporting refugees to nearby Greek islands.

The evacuation lasted for days. Among those evacuated was the future billionaire Onassis, who was 18 at the time. Out of Izmir’s 500,000-strong non-Muslim population, 320,000 were evacuated. The rest either died in various ways or were deported to the interior. Thus, “Infidel Izmir” was now a “national” city.

Tally and Cause

In the secret parliamentary discussions dated November 29, 1922, where the Izmir fire was discussed, it was stated that more than 20,000 homes had burned down and the damage exceeded 300 million gold liras. It was said that many officers, and even army commanders, participated in the looting of Izmir; that Sakallı Nureddin Pasha had safes blown open with bombs; and that no one knew where he kept the money.

In the Izmir fire, it was not the Muslim quarters but mostly the Armenian and Greek neighborhoods that were destroyed; looting and massacres also occurred. The aim was ethnic cleansing. The already dwindling Greek and Armenian populations of Western Anatolia had to be completely purged. This was the result of a political calculation.

Indeed, the reason for the Greek occupation of Izmir in 1919 was its then large Greek population. More importantly, since the era of the Committee of Union and Progress, Izmir and its surroundings were considered a refuge for Greeks who had been expelled from the interior of Anatolia and lost their homes and lands. Upon victory, it was decided that the Greek and Armenian presence in the Aegean should be eliminated. From a certain point of view, this was a logical decision.

There is also an emotional side to the matter. Five years before the Izmir fire, in 1917, the fire in Thessaloniki had completely destroyed the vast Turkish and Jewish neighborhoods. Not only that, but the population was also expelled, and a brand-new city was built in its place. Because, just like the houses, the title deeds had also burned. This newly constructed part of the city was allocated not to the native Turks and Jews, but to Greek refugees expelled from Anatolia. The city was thus transformed into a Greek city.

For Türkiye’s psychological foundation, the Thessaloniki fire was a horrific event. At that time, much of the country's educated and wealthy elite were from Rumelia (the Balkans), most of them from Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki, lost in 1913, was virtually the heart of Rumelia.

Thus, the burning of Izmir was, to a large extent, the revenge and retaliation for the Thessaloniki fire. The underlying plan was to cleanse Western Anatolia of Greeks. Without property, no claims could be made. Otherwise, Nureddin Pasha was merely an executor. Under such conditions, it is inconceivable that he could have acted independently from the government and the commander-in-chief. The event was the product of a collective decision.

There are extremely detailed reports sent by local correspondents in the foreign newspapers of the time. The famous writer Ernest Hemingway was also there as a war correspondent. Dozens of memoirs by those who lived through the event have been published. Therefore, abroad, there is no doubt about who burned Izmir. Giles Milton’s book “Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922” narrates those days beautifully.

You Follow Orders, So Do I!

Various theories were put forward as to who started the fire: frenzied irregulars who entered the city before the army; Armenians or Greeks who started it so that their property wouldn’t fall into Turkish hands; Armenians who set it to provoke the Allies into acting against the irregulars; Armenians who wanted to destroy the ammunition stored in their houses; Turks who wanted revenge against the Armenians and Greeks and to cover up the traces of the massacres.

The fire broke out after the city was recaptured. There is also the belief that it was started by Nureddin Pasha. Indeed, Nureddin Pasha, known for his arrogance and harshness, and criticized heavily by M. Kemal for his despotic manner, was of the kind capable of doing anything. Eyewitnesses later recounted that barrels belonging to the Smyrna Petroleum Company were brought there by soldiers, that each barrel placed every 200 meters was guarded by two soldiers, and that later gasoline was sprinkled on roofs and walls, and long sticks with cloth at the ends were dipped into cans and thrown into houses.

Izmir firefighters later testified to this in court. One firefighter even recounted that when he said to a soldier, “We’re putting it out and you’re setting it on fire,” the soldier replied, “You follow orders, so do I.”

The End of an Era

It is said that M. Kemal, who had said before entering the city, “If

anything happened to this city, I would be very upset,” later told the

young officers with him as they watched the fire:

“Lads, look

closely at this scene! These flames mark the end of one era and the beginning

of a new one. While all the sins of the last century of the Ottoman Empire are

being cleansed by this fire, the foundation of the new Turkish State and the

rise of the Turkish nation are also being declared to the world.”

The reports prepared by foreign inspectors based on documents and eyewitness accounts, which stated that the city was burned by the Turks, were not taken into account by Admiral Bristol. After conducting its own investigation, England brought the incident to court. The commander of the Allied forces, French Admiral Dumesnil, said to M. Kemal Pasha, “Many believe the fire was started by the Turks. Would you deny this?” and received only the response, “Yes, this fire is an unpleasant incident.” The matter was not pursued during peace negotiations and was dropped. But Izmir, one of Anatolia’s richest and most beautiful cities, lost its former glory.

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025

-

WHO BETRAYED PROPHET ISA (JESUS)?26.11.2025