IT WAS AN ART OF EXECUTIONER...

Living in society requires law; law, in turn, requires punishment when necessary. The executioner’s duty is to carry out the punishment.

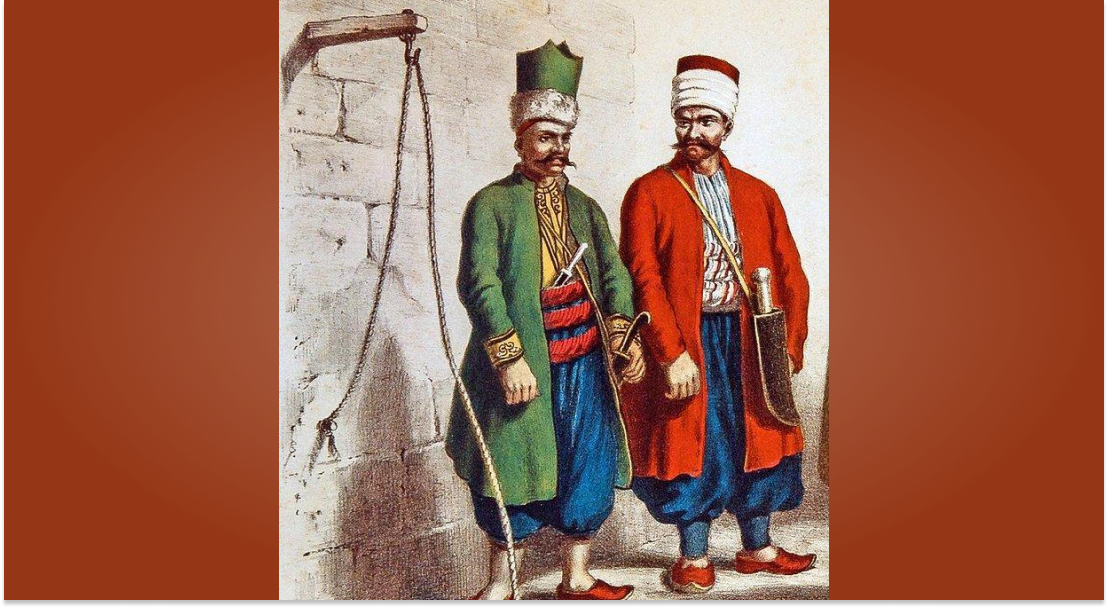

The word “Jellad”, which the Ottomans gave to the person who executed the crime, means one who beats with a stick. Execution means following the criminal. In Arabic, punishments are called "uqubat", which has the same meaning.

In a time when corporal punishment was the norm, punishments were generally beatings. When one thinks of an executioner, they usually think of a person who executes the death penalty, but that’s not entirely true. An executioner is a kind of guard, performing the duty of an execution officer.

Falling in Love with the Executioner

Although it was a feared job and executioners were dreaded people, it was a necessity. The famous saying goes, “If not for the Sultan’s decree, the executioner would not err.”

It is known that during the era of bliss the Companions (Sahaba) of the Prophet like Ali ibn Abi Talib, Zubayr, Miqdad, and Muhammad ibn Maslamah did this job. According to Evliya Çelebi, Eyyub Basri, the master of executioners, would recite Surah al-Fatiha after his work and advise those present, "Take heed of this man!"

In literature, it has become customary to call a merciless lover an executioner. One might remember the line from Kemani Tatyos, Ottoman composer, “What blood the executioner’s eyes have shed in Kağıthane.” There is also the expression “falling in love with one’s executioner” for those who have a morbid attachment to someone who has harmed them. (Kağıthane is the name of a popular recreation area during the Ottoman period.)

In Ziya Pasha’s verse describing the chaos of battle, he says: “Imagine the dreadful scene of the battlefield/ Where in a moment a thousand victims and a thousand executioners appear!” Aren’t people the executioners of each other?

Pasha’s Executioner

In the Ottoman Empire, the court that handed down the punishment would deliver the criminal to the subaşı, the police chief, who would have the punishment executed by the executioners under his command.

Execution was a job that required skill. It was expected that the executioner perform his duty without causing turmoil and without giving the condemned too much pain. Hence, these individuals were called masters of the political arena.

The division of executioners responsible for carrying out punishments in the palace was under the command of the head gardener (bostancıbaşı), who was directly attached to the Sultan. In the absence of these in the palace and in urgent cases, gardeners responsible for the palace gardens and shore security performed this duty.

Two gardeners (bostancı) were always on duty. Additionally, 4-5 helpers from logistical unit of the army reponsible for tents, would wait near the doorkeepers’ section in the palace. Executioners could also be chosen from left-handed guards, doorkeepers, or even inner palace pages. Pasha’s executioners accompanied governors and commanders on campaigns.

Pasha’s executioners accompanied governors and commanders on campaigns. In very private and sensitive executions, deaf and mute executioners were employed to prevent them from being swayed by conversations with the convict. It is not true that those who were to become executioners had their tongues cut.

.jpg)

Sherbet of Death

In Islamic law, the death penalty is very rare. In the Ottomans, it was generally given to statesmen who committed major political crimes or mistakes.

The death penalty was carried out by beheading, the fastest and least painful method of execution. Hanging was considered torture and against human dignity. Only bandits caught in clashes could be hanged for display.

The punishment would be respectfully communicated to the convict whose "removal is decreed" by kissing the hem of the garment by the head gardener. Consoling words would be spoken. The convict was allowed to take ablution and perform two rakats of prayer. This also applied to ordinary convicts.

The convict was taken to the Fish House (Balıkhane) on the Marmara coast of the palace by the head gardener. In palace jargon, "being taken to the Fish House" meant execution. At the point where the palace walls joined the Byzantine walls, there was the Fish House Gate opening to Marmara, with the Fish House Pavilion above it; inside the gate was the Fish House Quarters. This was the farthest point from the inner palace. Ahırkapı Fishery, which caught fish for the palace, was in front of it.

The head gardener would wait for a pardon news; the punishment was not carried out immediately. If the awaited news arrived, cool sherbet (a sweet drink) in a porcelain cup would be offered to the convict. Then, the convict would be sent into exile with a boat that docked at the Fish House Gate.

If no news arrived, the convict would be presented with a sherbet of blood color. This was now the sherbet of death. The executioner carried out the sentence accompanied by two assistants. Unless the convict was of very high rank, the head gardener would not be present at the execution.

Pillar of Warning

The head of those executed in the provinces would be sent to the center in a honey-filled horsehair bag to prevent spoilage. After confirming the identity and finalizing the execution, it would be buried. Traditionally in Turkish people in a hurry are asked, "Are you taking a head to the Pasha?" for this reason. Some people's heads were displayed for a time (about three days) at the pillar of warning in front of the palace for public awareness, with a sign explaining the reason for the execution.

Even some high-ranking officials had their heads displayed, but not in front of the palace, inside it. The relatives of the deceased would give a tip to the executioner and take the body to bury it with a religious ceremony. Even if the person was a criminal, they were still considered to have human dignity, so throwing the body into the sea, dismembering it, or hanging it on a hook was not the issue.

The tales of such actions are fabrications of travelers. Historians like Evliya Çelebi, Ahmed Refik Altınay, and Reşad Ekrem Koçu, who are also famous for their vivid imagination and narrative abilities, should be regarded with caution.

With the Tanzimat reforms, political execution was abolished. The Janissary Corps along with the Executioner Corps was dissolved. Executioner duties began to be contracted out for a fee.

Devoid of Light on His Face

The most famous executioner in Ottoman history (thanks to Evliya Çelebi) was Kara Ali, his assistant Hamal Ali, and later the chief executioner Suleyman.

Kara Ali, unmatched in mastery and personally seen by Evliya Çelebi who called him a master, served as an assistant to the chief executioner Suleyman Agha during Sultan Mustafa I’s time. After his death, Kara Ali served as the chief executioner during the reigns of Sultans Osman II, Ibrahim, and Mehmed IV. He was also Sultan Ibrahim’s executioner.

Although said to be emotionless, resolute, and merciless, he avoided killing Sultan Ibrahim, and only completed his task when threatened with a stick by the rebels. Afterwards, he left the job out of remorse. Evliya Çelebi described him as “a man devoid of light on his face, like poison. He wandered with his sleeves rolled up and chest bare all year round.” He often didn’t even ask who he was executing. When he went out, he carried a naked sword on his right shoulder, and an oiled noose hung from his belt. He wore a red felt executioner’s cap on his shaven head.

Strangely, the most famous executioner of the Republic era was also Kara Ali from Izmir, who hanged famous men. His interview was published in newspapers in 1950.

Executioner’s Auction

High-ranking execution prisoners would take off their valuable belongings before execution and give them as gifts to those present, asking for Surah al-Fatiha to be recited for them in return.

Most of the prisoner's belongings would be claimed by the executioner because many were slaves and therefore had no heirs other than the sultan. The executioners would auction these belongings once or twice a year, sharing the money like restaurant tips among themselves. However, the public did not see these items as auspicious, so they were sold cheaply. People would say "Did you buy it at the executioner's auction?" about cheap goods.

The historian Peçevi has an intriguing story: “Sultan Murad III’s favorite, the chief eunuch Gazanfer Agha, had an extraordinarily valuable gold-embroidered watch adorned with diamonds made by the famous watchmaker of the time, Rasim. When Gazanfer Agha fell into the executioner's hands during a military revolt, the watch, a fortune in itself, was put up for auction by the executioner and bought by Tırnakçı Hasan Pasha. Shortly after, he was also executed, and the watch was bought from the auction at a very low price by Kasım Pasha. A couple of months later, he too was executed. The watch was then purchased by Grand Vizier Derviş Pasha and gifted to his younger brother.

This young man, known as Civan Bey because he started service at a young age and whose real name was unknown, was the Sanjak-bey of Euboea. While sitting on the terrace of the mansion with Peçevi, he took out this watch from his bosom. The watch enthusiast Peçevi was amazed. When he said, ‘I have never seen such a beautiful watch in my life,’ Civan Bey told its story.

When Peçevi asked, ‘How could the Pasha give such a watch as a gift? One wouldn’t give this even to an enemy,’ the Bey removed the diamonds with his dagger and broke the wheels with a hammer, throwing them into the sea. The watch’s sparkle could be seen at the bottom of the sea.

Half an hour to an hour passed. A horseman arrived, informing the Bey of his dismissal. When the Bey was surprised, the horseman said, ‘Sir, Derviş Pasha has been executed. There is also an order for your execution. The gardener was sent with the order. Then, intercessors intervened and had you pardoned. I was sent with a second order. I reached those assigned to execute you just half an hour ago.’”

Gypsy Load

It is said that the executioners were of Gypsy or Croatian origin, but this is debatable. Nevertheless, most of the executioners during the republican era were Gypsies. As Nazım Hikmet wrote in 1933: “A dead man hanging on a rope/My heart cannot accept this death/But rest assured my darling/If the poor hand of a Gypsy/Resembling a hairy, black spider/Is to slip the noose around my neck/They will look in vain into Nazım's blue eyes to see fear!”

In 1961, Kemal Aysan, who hanged Adnan Menderes and his friends; and Hüseyin Yalçın, who hanged convicts during the September 12 coup, were such.

Executioner's Fountain

In the courtyard of Topkapı Palace, the fountain near the wall extending from the Fountain Gate to the Middle Gate was called the Executioner's Fountain or the Politics Fountain. It was in a ruined state, with its spout broken and parts of it damaged.

Allegedly, execution sentences were carried out in its trough, or the executioner would wash his equipment there after the deed; the head would be placed on the column-like stone in front. However, executions were not always carried out in the same place. It was usually in the Fish House.

Before Kaiser Wilhelm’s visit in 1889, Sultan Abdulhamid II had the fountain removed to avoid any unpleasant thoughts while touring the palace. The chronicler Abdurrahman Şeref Bey recounts that the “unlucky fountain, a silent witness to many cries and tears,” was not destroyed but moved inside the Imperial Gate and replaced by the Hamidiye Fountain. The wall fountain shown to visitors as the “Executioner's Fountain” is this one.

Executioner's Cemetery

There was an executioner's cemetery behind Karyağdı Hill in Eyüp. It was isolated and abandoned. Some of the tombstones, made of large square-cut limestone, were nearly two meters tall. They were all uninscribed.

Reşat Ekrem Koçu claims that executioner graves were uninscribed. If true, it might have been to forget their names and spare their families from shame. However, not every uninscribed stone is an executioner’s grave.

Later, some were lost, and some ended up among other graves. Nowadays, only a few stones remain. There are also a few executioner’s graves at Tokmaktepe, in the courtyards of Baba Haydar and Nişancı Mustafa Pasha Mosques in Nişanca, and in the courtyard of Gaysunizade Mosque in Beyoğlu.

Önceki Yazılar

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025