.jpg)

VISA REQUIRED: TRAVELING TO ISTANBUL DURING OTTOMAN ERA

As the capital city of the empire, Istanbul was administered under strict rules and travel to the city was regulated. Different permits would be issued depending on whether you wanted to visit and or to settle down. The city population was also strictly maintained in order to avoid food shortages and keep the peace

Istanbul was always administered differently than the other Ottoman provinces. In fact, all capital cities in the Middle Age and the New Age had a different status than the others. As it was regulated by specific principles for people either wanting to settle down or to do business in the Ottoman capital, food supply and discipline were extra important as it was the heart of the empire.

In the case of any problems in the food supply or public order, political authorities were in serious danger and social stability was easily distorted. For this reason, the food supply in Istanbul was under extra-firm control. Due to the harsh weather conditions during the time of Sultan Osman, II, the Bosporus froze over and merchant ships could not approach the port. The expense involved in rectifying the situation ended up costing the sultan the throne and his life.

Unlike the other Ottoman cities, Istanbul did not have a governor or city council. Its people weren't responsible for military service. Educated men in the city served as civil servants, and non-Muslims were busy with the arts and business. Even the social life, accent and the customs were different.

Istanbul had an unnamed privileged status and its population was fixed. It was difficult to settle down in Istanbul. Those who visited or passed through Istanbul with private permission due to reasons like pilgrimage, partition of inheritance or funerals had to leave the city as soon as their reason for visit ended.

As facilities like shipyards always needed workers, Istanbul constantly had temporary citizens who came to the city for work. These people were called "bekar uşakları," meaning young bachelors. They had to live at the famous "bachelor rooms" of the time, which were regulated by the government.

A nested system

In the classical era of the Ottoman Empire, any villager who rented state land in Rumelia and Anatolia didn't have the right to leave the land before the rent period came to an end. Otherwise, the villager was brought to the land again and served with a fine. The state income was generally bound to soil products. This rent, which corresponded to one-tenth of general income, and the other taxes were collected by the military landlords called cavalrymen. These cavalrymen hosted soldiers in return for taxes. Land management was nested with the military and the financial system.

Gaining permanent residence in the city was very difficult in order to avoid problems with the public order and the food supply. Preventing the migration from the villages to the cities was state policy. Historian Gelibolulu Ali, who lived in the time of Suleiman the Magnificent, wrote a work titled "Nasiha al-Salatin" ("Advise for Sultans"), in which he gave advice to statesmen.

In the book he says, "The administrators must prevent migration from the villages to the cities. If these people leave their hometowns, the lands of those towns cannot be cultivated. Hence, cavalrymen lose money as the taxes collected from the villagers will stop. All these are a blow to national defense. The villagers migrating to the cities worsen the living conditions of the city people. They work in the cities, but do not pay taxes. What the administration has to do on the issue is either send them back to their villages or force taxes on their businesses, which will be under firm control."

Domestic passport

In the 17th century, villagers started to leave their villages due to war, rebellion and famine and settled down in the protected cities encircled by walls. To prevent Istanbul from being affected by these migrations, controls at the city entrances and exits were tightened.

The Ottoman kadi (judge) was also the mayor of the city he served. Sultan Mahmud II (1808-1839) founded the municipality organization by taking this mission from the kadis. He also ordered that dilly-dalliers won't be allowed in the city.

With the first step, bachelor rooms, most of which turned into prostitution spots, were taken under control. Most of these bachelors started to serve as janissaries. These rooms were demolished one by one during the abolition of the guild of janissaries (1829) and their residents were expelled from the city.

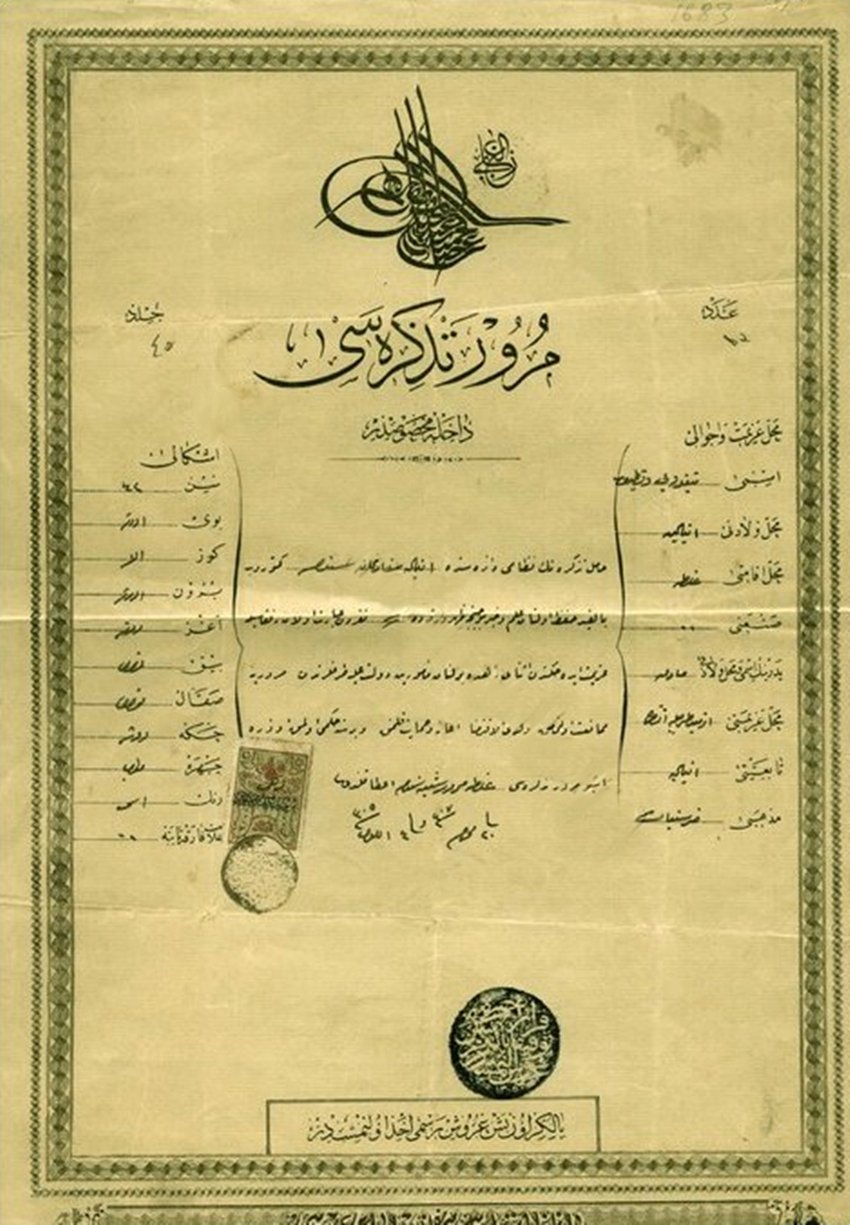

According to the new regulations, those who did not have a domestic passport, "mürur tezkeresi," couldn't be taken within the borders of Istanbul. People could get these domestic passports from their hometowns and their purpose of visit had to be written in the passport. Those coming from Rumelia used the Küçükçekmece gate while those coming from Anatolia entered the city by using the Bostancıbaşı Bridge.

Those who entered the city by using any gate other than the ones located at the two far edges of Istanbul were punished. Passports that didn't faithfully represent the carrier and their situation were scrutinized by the municipality and these people weren't taken into the city if necessary. The controls were tighter for Albanians and Kurds coming to Istanbul from highlands.

Collective responsibility

Visitors who showed their domestic passports at the official gates had to apply to the municipality to be registered with their current appearance. They had to hand over their weapons if they had any. These people were accommodated at the bachelor rooms allocated by the state. As visitors coming from the Aegean Islands often came into conflict with those coming from Anatolia and Rumelia in terms of personality, they were hosted in different places.

After starting a job they were familiar with, they had to provide a guarantor and register them. If they couldn't find a job suitable for their profession or they were extra-personnel, they were sent back. Those that went back had to get a new domestic passport from the city administration. If these bachelors lost their lives in Istanbul, their guarantors had to register them to the roll.

If they were involved in a crime, also their guarantors were responsible for the crime as the guarantors had to inform the relevant authorities if they witnessed any improper behavior.

Local authorities were responsible for controlling the domestic passports at various intervals. They were in charge of the public order of their neighborhood. In Ottoman neighborhoods and villages, there was a principal of collective responsibility. Everyone was the guarantor of their neighbors. They had to inform the state in the case of any improper situation they witnessed.

End of the dream

Domestic passport enforcement was extended to all of the Ottoman Empire after 1908. According to the regulation, dilly-dalliers, beggars and suspects could be expelled from the cities they lived in by court decision. The exemption from military service of Istanbulites was abolished in 1909.

However, tens of thousands of Rumelia people migrated to Istanbul after the succession of wars. Then, Caucasian immigrants followed them. To top it all, anti-Bolshevik Russians who escaped from the Russian Revolution rushed into the city. Istanbul was swarmed with immigrants.

The Government of the Committee of Union and Progress, which thought that they were capable of governing the state, failed to handle the issue. Parks, mosques, schools and even deserted houses were given to the immigrants. The city's population increased rapidly. Public order was disturbed. Famine and the black market rose in the city due to the increased prices. Epidemics appeared.

Hence, the dream of a sweet era came to an end. Istanbul, that dream city, irreversibly lost its old magnificent beauty.

Önceki Yazılar

-

DEATH IS CERTAIN, INHERITANCE IS LAWFUL!25.06.2025

-

THE SECRET OF THE OTTOMAN COAT OF ARMS18.06.2025

-

OMAR KHAYYAM: A POET OF WINE OR THE PRIDE OF SCIENCE?11.06.2025

-

CRYPTO JEWS IN TURKEY4.06.2025

-

A FALSE MESSIAH IN ANATOLIA28.05.2025

-

WAS SHAH ISMAIL A TURK?21.05.2025

-

THE COMMON PASSWORD OF MUSLIMS14.05.2025

-

WERE THE OTTOMANS ILLITERATE?7.05.2025

-

OTTOMAN RULE BENEFITED THE HUNGARIANS30.04.2025

-

An alternative state to Istanbul in Anatolia: THE ANKARA ASSEMBLY23.04.2025