.jpg)

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II

Sultan Mehmed II is regarded by historians as one of the greatest statesmen not only of Turkish history but also of Islamic and even world history. In military affairs and politics, in science and culture, and in the arts and literature, his depth is such that even today he has very few equals. Thus, he has been presented as a model for Renaissance rulers. It was he who transformed the Ottoman State into an empire, both in terms of territory and organization.

Tolerance or Forbearance?

When the Ottomans conquered a land, the people of that land were considered Ottoman citizens. By pledging to recognize Ottoman sovereignty and to abide by its laws, they continued their previous lives. The Ottoman State, in turn, guaranteed the lives, property, and freedom of religion of these non-Muslim citizens, who were called dhimmis. In the eyes of the law, there was no difference between a Muslim citizen and a non-Muslim citizen. This matter was neither a favor granted by the state or the ruler to non-Muslim subjects, nor a requirement of an international agreement. It was an internal legal arrangement based on Islamic law (sharia). From this perspective, no government could restrict or abolish it; nor could non-Muslims renounce these rights.

Non-Muslims in the Ottoman lands were not minorities but citizens. The concept of minority (aqalliyyat) entered Türkiye in the twentieth century with the notion of the nation-state. For in the modern world, minorities mostly come into conflict with the majority. Whereas in the Ottoman system, each community lived within its own sphere; work, advancement, activities, and social mobility were carried out within that sphere. For example, the ideal of an Armenian youth was to enter the administrative class within his own community. Passage between spheres occurred only through conversion to that religion. The notion that each community should operate within its own boundaries remained an unwritten principle of the empire until its end. The millet system was an administrative strategy for managing a multi-religious empire. The word "millet" means “religious community” or “people” in Turkish. It continued in various forms for more than five centuries. This period was far longer than the performance of liberal democracy or the nation-state.

Marriage between members of different communities was unthinkable; living in the same neighborhood was rare; their relations were limited. Therefore, problems such as conflict, strife, identity assertion, and assimilation did not arise among them. If they did arise, the government prevented them. Thus was the “Ottoman Peace” ensured. What is meant here is not tolerance but forbearance (tasamuh). Tolerance carries a sense of endurance and thus a certain weakness. Forbearance, on the other hand, is better suited to expressing a benevolent patience within tolerance.

What Audacity Is This?

When Istanbul was conquered, there is a historic reply given by Sultan Mehmed II to those who proposed that non-Muslims be confronted with the choice of either converting to Islam or leaving the city: “What audacity it is to attempt to protect the true religion, Islam more than the Exalted Lawgiver (Shariʿ al-Taʿala, Allah) Himself” (That is, while Allah, the owner of the religion, exists, is it your duty to protect Islam? Whereas He has not willed this.)

A similar incident occurred in the Balkans. When Sultan Mehmed II’s conquests in Rumelia reached the Serbian border, Branković, the king of the Serbs of the Orthodox denomination, found himself caught between the Catholic Hungarians and the Ottomans. He sent one envoy to Sultan Mehmed II and another to the Hungarian king Hunyadi János. He asked how the Serbian people’s religion would be treated if Serbia were left under their rule. The Hungarian king said that he would demolish all Orthodox churches and build Catholic churches in their place. Sultan Mehmed II’s reply, as always, was unparalleled: “I would permit a church to be built next to every mosque, allowing everyone to worship according to his own religion.” Thus, Serbia came under Ottoman rule.

The Patriarch Received Standing

When the Ottomans besieged Istanbul, the Orthodox population was divided over the issue of uniting with the Catholics. Patriarch Athanasios II had been deposed for opposing this, and the office was vacant. The Byzantine grand vizier Notaras said, “Rather than seeing a cardinal’s hat (that is, Catholic domination) in Istanbul, I prefer the Turkish turban (Muslim domination).”

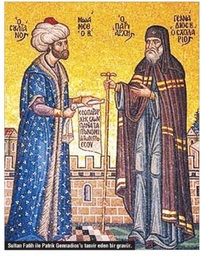

Sultan Mehmed II appointed a reclusive priest named Gennadios, who opposed the union, as Ecumenical Patriarch (patriarch of all Orthodox Christians) for life and granted him a place in the protocol with the rank of vizier. During the conferral of office, the traditional ceremonies inherited from Byzantium were applied. The sultan received and escorted the patriarch while standing. He presented him with a staff and a horse from the imperial stables.

For this reason, Sultan Mehmed II is regarded by most historians as the second founder of the Patriarchate and as the Eastern Roman Emperor. For the emperor is the sole authority entitled to appoint the patriarch. The sultan had now taken the place of the emperor. Thus, all Orthodox Christians outside Russia came once again under the influence of the Patriarch of Istanbul.

The patriarchate, which was initially located in the Draman district, was moved to Fener in 1587. Since then, it has been called the Fener Patriarchate by the Turks. Sultan Mehmed II’s protection of the patriarchate provided the Ottomans with great political and social advantages in the Christian world. Even today, behind America’s preference for the Patriarch of Fener over the Patriarch of Moscow lies this policy.

No Punishment Without Law!

The Hurufis, who belonged to the extremists of Shiism and claimed that the Qur’an has an esoteric (hidden) meaning which only they could understand through certain codes in the letters of the Qur’an, and who believed that Allah manifested Himself in the form of Ali ibn Abi Talib, had long been active in Anatolia. Sultan Mehmed II, instead of immediately punishing this group whose activities and beliefs were clearly contrary to Islam, convened a scholarly council in the palace under the leadership of one of the great scholars of the time, Fakhr al-Din al-Ajami. The leading figures of the Hurufis were invited to this council.

When Fakhr al-Din al-Ajami refuted their claims one by one from a scholarly perspective, Sultan Mehmed II ordered that they all be punished. By this action, which was far removed from arbitrariness and exemplary in its adherence to law, he both prevented the spread of Hurufism and rendered an important service to the unity of the nation and the preservation of the religion. Today, some accuse the sultan of being a Hurufi, or even of sympathizing with Christianity, because of this stance—which is ridiculous.

Önceki Yazılar

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025