.jpg)

THE ABBASIDS IN ANATOLIA

1258 is one of the disastrous years of Islamic history. The Mongol commander Hulegu, after destroying Muslim Turkish cities with his army, came to Baghdad. He burned and demolished the city. He massacred its people. He captured the 37th and last Abbasid Caliph al-Musta‘sim, and although he pleaded for mercy, he was trampled to death under the feet of horsemen in a horrible manner.

Thus, the centuries-old Abbasid Caliphate collapsed. Hulegu had all members of the Abbasid family, young and old, male and female, massacred—among them about forty princes in their cradles inside the palace. The books in the libraries were thrown into water. From their bindings, the soldiers made rawhide sandals. For days, the Tigris River flowed first with blood, then with ink.

.jpg)

LIKE A NOVEL

Only two young princes survived the massacre. One of them happened to be in Damascus. The other fled with a loyal servant, undertaking an adventurous journey, and secretly took refuge in Cairo. Hulegu sent two divisions of soldiers after them. The division sent to Damascus martyred the prince there. The division sent to Egypt was crushed by the Mamluk army. This was the first defeat of the Mongols.

The prince in Egypt was Ahmad, the grandson of the former caliph al-Mustarshid. He hid for a while. During this time, Egypt began to experience an unprecedented abundance. Everyone was curious about the reason for this. One day, when he went to a mosque with his servant, some people recognized the prince. These were people who had seen both him and his servant in Baghdad, where they had been as merchants and travelers. The servant, in panic, denied it. To those who did not accept the denial, he pleaded and begged them to remain silent.

Another day, during Friday prayer, the Mamluk Sultan Baybars saw him. The brightness on the prince’s forehead and the nobility on his face caught his attention. He held his hand and did not let go for a long time. When he persistently asked who he was, the prince was forced to confess. The others who recognized him also confirmed it. The servant was frightened but could say nothing. The Sultan took him to his palace. He dressed him in a kaftan (a long belted tunic) and seated him on a high throne. In 1261, the entire population of Egypt pledged allegiance to him as caliph. It became clear that the abundance was coming from this. They gave him the name Ibn al-Barakat Ahmad al-Mustansir Billah. His name was recited in Friday sermons (khutbahs). Coins were minted in his name.

The caliph left the government in the hands of the sultan. He himself remained in a symbolic position. It continued like this until the end. When the Mamluk sultans ascended the throne, the caliph would recognize this appointment. The people and most of the sultans showed him respect.

FROM CAIRO TO HAKKARI

Toward the end of the Mamluks, the caliph was Ya‘qub al-Mustamsik Billah. He had been caliph since 1497. Both his mother and father were Abbasids, a rare situation among the Abbasid caliphs. When he became caliph, he was 50 years old. He was a student of Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti. Over time, as he grew older and his eyesight weakened, under the pressure of Sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri, in 1508 he handed the position over to his son Musa III al-Mutawakkil ‘ala Allah and withdrew into seclusion.

Caliph Musa was with the sultan at Marj Dabiq and sought refuge with Sultan Selim I. As a result, his father was re-declared caliph in Cairo. Caliph Musa came to Cairo with Sultan Selim. Sultan Selim left Caliph Ya‘qub in Cairo and took his son Musa with him to Istanbul. Ya‘qub died in 1521.

The last two rulers of the Circassian Mamluks, Qansuh al-Ghawri and Tumanbay, were not respectful to the caliphs. When Sultan Selim I conquered Egypt, the caliph met with him. Through the caliph, the sultan proclaimed to the people that no harm would come to anyone’s life or property. The caliph gained so much prestige that even the Mamluk beys sought refuge with him. Sultan Selim treated the caliph with respect, accepting all his requests and intercessions.

The caliph came to Istanbul with his family. Some relatives who remained in Egypt complained that the caliph had seized people’s property. As a result, the caliph’s prestige declined. At one point, he was even placed under residence at Yedikule (the Seven Towers Fortress). When Sultan Suleiman I ascended the throne, he released him. Some sources say that he returned to Egypt and died there in 1543.

In the book Mukhtasar Ahwal al-Umara it is written that he joined campaigns with Sultan Suleiman I, was wounded in both hands, and received the title Asad-i Ghazi (the Lion Warrior) from the sultan. Upon his request, he was given the Sanjakbeylik of Hakkari, and his descendants carried out this duty for centuries. Considering that his descendants always lived in this region, this account is not unfounded.

They joined Ottoman campaigns with units formed from Kurds. They protected the borders and stood against Iranian attacks. Most of Kurdistan was subject to them. They were known for their justice, generosity, and piety. In some regions, among Kurds who had not yet become Muslim and among Syriac Christians, they worked for the spread of Islam and Sunni belief. They built many charitable works in the land. Among them, Ibrahim Han, Izzeddin Shir, and Zeynel Bey are well known. Princes from the family were also appointed as rulers of nearby towns and cities. From here, they spread to surrounding areas. Since their first settlement was in the village of Irisan between Hakkari and Başkale, this family was also called the Beys of Irisan.

THE END OF THE BEYLIK

One of the last beys of Hakkari, Nurullah Bey, was imprudent. He had turned away from his family and other beys. In 1843, with the help of Bedirhan Bey, the emir of Cizre (Botan), some tribes attacked Christian Nestorian villages, committing massacre and plunder. The incident escalated. The British sent a note of protest to the Ottoman government. The Ottoman army came to the region. Bedirhan Bey was defeated, captured, and sent to Istanbul. Nurullah Bey was his ally. He retreated in fear and, upon the advice of Sheikh Sayyid Taha al-Hakkari, one of the great scholars of the region, he surrendered. He was exiled to Crete. Thus, in 1849, the autonomy of Kurdistan was abolished, and the Province of Hakkari was established. A centralized administration was established throughout the empire. Those from the Irisan family who had wealth were able to rule for a while longer as local beys. Some lived ordinary lives, blending in with the people.

The Abbasid family continues in the East even today. Ismail Fakirullah, one of the saints of Siirt, was from this family. The Arvasi family, descending from Imam Husayn and producing great scholars in recent centuries such as Sayyid Sibghatullah, Sayyid Fahim, and Sayyid Abdulhakim Arvasi, is maternally descended from the Irisan Beys. Former Erzincan deputy Sadi Abbasoğlu and, as far as I know, former minister Abdulkadir Aksu also descend from the Abbasid beys.

The Abbasid family is one of the longest-lived dynasties recorded in history. It held the caliphate in Baghdad for 508 years, in Cairo for 255 years, and ruled a beylik in Eastern Anatolia for 330 years, setting a record. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) had foretold that the descendants of his uncle Abbas would hold the caliphate for centuries.

THE SACRED RELICS

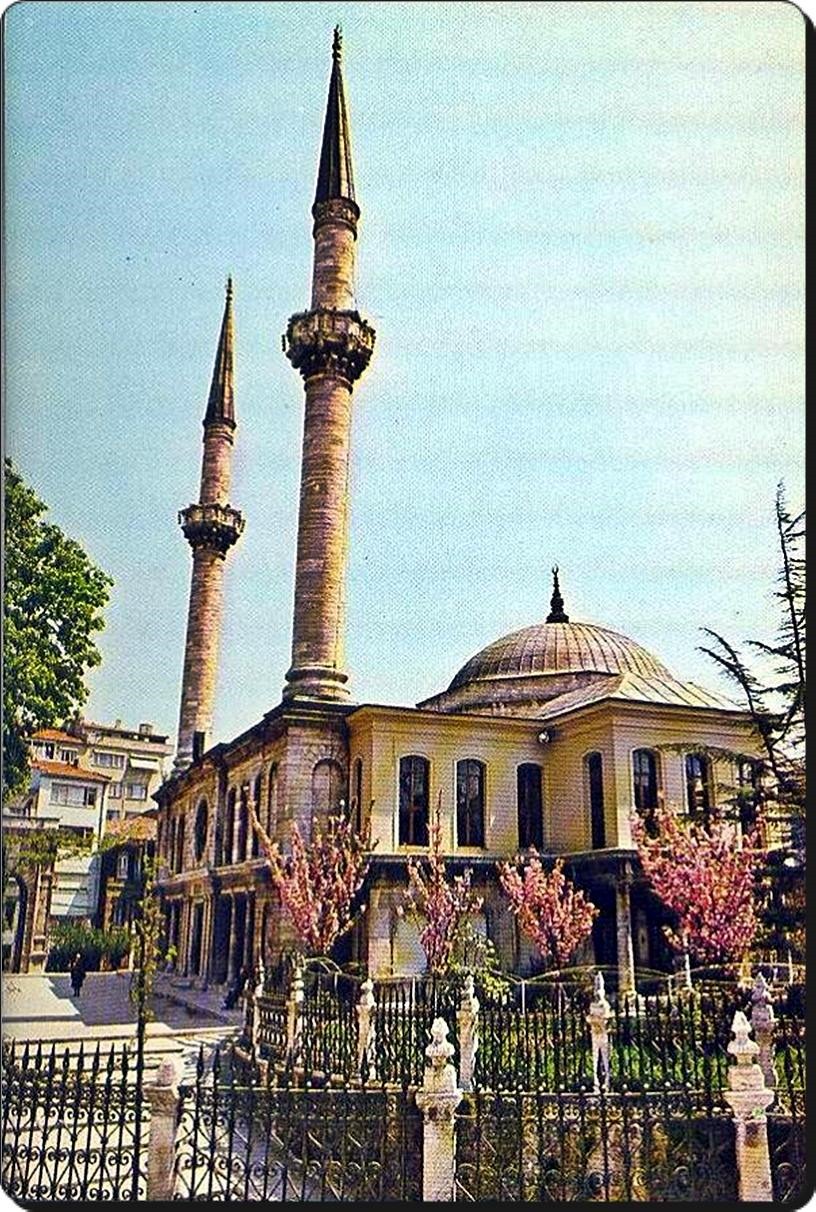

The last Abbasid caliph entrusted some sacred relics to Sultan Selim I. The famous Khirqa al-Sharifa (the Noble Mantle) that the Prophet Muhammad had gifted to Uways al‑Qarani also reached this family. From the descendants of Uways al‑Qarani’s brother and a resident of the Irisan beylik, Shukrullah Efendi brought it in 1618 and presented it to the Ottoman Sultan Osman II. Sultan Abdulmejid had the Hırka-i Sharif Mosque built near the Fatih district for this mantle. Every year during the holy month of Ramadan, it is displayed to the public inside a glass case by the descendants of this Shukrullah Efendi.

In addition, the left shoe of the Prophet Muhammad (the Na‘layn al-Sharif) was also in this family, until it was entrusted to Sultan Abdulaziz in 1872. The other shoe had been delivered during the time of Sultan Selim I by Caliph al-Mutawakkil. A turban (the Taj al-Nabawi) and a banner (Liwa’ al-Sharif) belonging to the Prophet are still preserved by the family. The banner of Ali ibn Abi Talib also in the possession of the family.

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025

-

WHO BETRAYED PROPHET ISA (JESUS)?26.11.2025