IMAMS AND MUFTIS AS OFFICERS IN THE OTTOMAN ARMY

The sense of religion and the love of homeland and nation were the most important factors that motivated armies on the battlefield and drove them from victory to victory. Armies strong in morale were able to defeat forces superior to them under difficult conditions.

The mission of the Ottoman State was shaped by the spirit of ghaza (holy war). Ghaza means spreading the name of God everywhere. Shouting “Allah! Allah!” during the attack symbolized this. Whoever participated in it was called ghazi (holy warrior). Whoever died in ghaza was called martyr (shahid), because he beheld Paradise. No one else was called ghazi or shahid. It was this spirit, says the historian Wittek, that made the Ottomans victorious on three continents.

For this reason, adherence to religious principles occupied an important place in the Ottoman army. Importance was given to soldiers and officers performing their worship and avoiding sin. Pious soldiers and officers were promoted and rewarded; those who behaved carelessly could not remain in the army. The wisdom behind calling the army the Prophet’s Hearth was also this.

Congregational Prayer in the Barracks

In the barracks at Aksaray of the janissaries, who constituted the professional part of the Ottoman army, there was the “Orta (Company) Mosque.” Soldiers performed their prayers there together with the janissary agha and in congregation. In the Janissary Corps, the duty of imam was carried out by the “Imam Hadrat al-Agha” and his assistants; a mudarris (religious teacher) also gave lessons there. In each janissary company (orta), there was an imam appointed to provide religious knowledge to the soldiers, lead prayers, and perform funeral services.

According to tradition, at the founding of the Janissary Corps, Hacı Bektaş Veli (or a person affiliated with him) prayed for this army and gave it the name “janissary” (yeniçeri). Çeri means soldier in Turkish. This event also gave rise to the dominance of Sufi culture in the Janissary Corps. There were also army sheikhs, whose duty was to inspire zeal in the soldiers during war.

In the new army established by Sultan Selim III, called the Nizam-ı Cedid, an imam was appointed to each company, and it was ordered that prayers be performed in congregation and that the famous catechism book known as Birgivi’s “Vasiyyetname” be read to the soldiers.

Sultan Mahmud II abolished the Janissary Corps and established in its place the army called Asakir al-Mansurah al-Muhammadiyyah (Victorious Soldiers of Prophet Muhammad). In each company, it was decided to have an imam and to open a school where soldiers would be taught the Qur’an and catechism every day. He also had the great Hanafi scholar Imam Muhammad’s book on the law of war, Siyar al-Kabir, translated into Turkish and ordered it to be read to the soldiers.

Religious Lessons in Military School

From the time of Sultan Mahmud II onward, the Ottoman army was reorganized. The custom of having imams and muftis in regiments continued. In the first battalion of the regiments, the regimental imam was placed between the rank of captain and senior captain (kol aghassi). They had their own uniforms. They led congregational prayers, preached and advised the soldiers, and performed funeral services. When promoted, they became regimental muftis. Their rank was between senior captain and regimental treasurer (alay emini).

In the Tersane Mosque, which was the naval counterpart of the Orta Mosque, there were officials such as imam, khatib (preacher delivering the Friday sermon), muezzin, vaiz (moral preacher), second imam, second muezzin, and Juzʾkhan (person who recites portions of the Qur’an).

Ship imams led congregational prayers on board, taught the Qur’an and catechism to soldiers, preached, performed funeral services, and during war sought to raise the morale of the soldiers. Ship imams were selected by the Naval Council from candidates belonging to the learned class (ilmiyye) by examination. They wore turban and robe, with embroidered bands on their sleeves indicating rank.

The Ottoman navy would anchor in port on days such as Christmas and Easter so that non-Muslim officers and soldiers could go home or attend services. In the newly established military schools, apart from Arabic and Persian, there were also lessons in Ulum al-Diniyyah (religious sciences, basic Islamic knowledge), Sirat al-Nabi (the life of the Prophet), and Ilm al-Akhlaq (the science of ethics, teaching good morals).

In the Military Academy (Harbiye Mektebi), in addition, jurisprudence (fiqh) and principles of jurisprudence (usul al-fiqh) were taught. At graduation, cadets placed their hands on the Qur’an and swore an oath to God.

Moral Officers

The period of the Second Constitutional Era, when bureaucrats and soldiers loyal to Sultan Abdulhamid II were purged and replaced with Unionists (members of the Committee of Union and Progress), was a period when devotion to religion in the army visibly decreased. Officers did not allow soldiers who wanted to pray, and they openly ate during Ramadan; this constituted one of the causes of the 31st March Incident (1909). Memoirs written about the World War I greatly help in understanding the religious state of these officers.

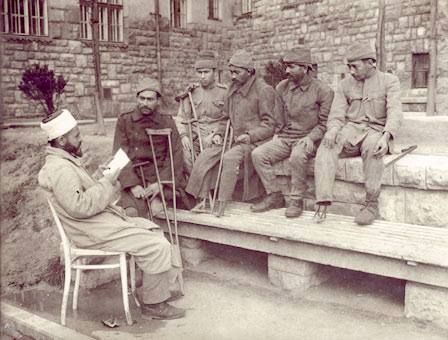

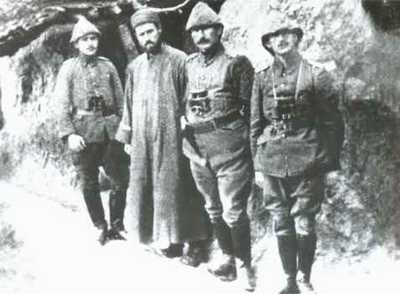

There are many memoirs concerning the courage and heroism of military imams and muftis during battle. The last regimental mufti in the army, Hafız Hasan Feyzi Akıncı (1885–1961), was my great uncle. He graduated from the Fatih Madrasa; after serving as judge (qadi), he joined the army; when Edirne was recaptured in the Balkan War, he led the first Friday prayer there. Because of his services in transporting ammunition from Istanbul to Anatolia, he was awarded the Independence Medal. In the republican period, he was transferred to the personnel class, and when he retired in 1945, he was a lieutenant colonel in the 52nd Regiment in Antalya.

After the establishment of the Turkish Republic, due to the religiosity of Chief of General Staff Fevzi Çakmak, although the functions of religious officers in the army greatly diminished, their presence continued. “The Soldier’s Religious Book” by Hamdi Akseki, President of Religious Affairs, and “My Religion” by Şerafettin Yaltkaya were printed and distributed to soldiers. The tradition of oaths taken by soldiers and students upon the Qur’an and the prayers in oath ceremonies continued.

In the 1940s, when Fevzi Çakmak was retired, religious services in the army were suspended. When Türkiye entered NATO, the staff position of chaplain present in the American army was adapted into its own army, and theology graduate officers were appointed here, but of course, their involvement with religious affairs as in the old period was out of the question.

This position was renamed “moral officer” after the 1980 coup, and under the order of Land Forces Commander Kemal Yamak, mosques were built in all units and their responsibility was entrusted to soldiers knowledgeable in religion. Later, some of these were closed due to lack of congregation, and in some, it was ordered that entry in uniform was forbidden.

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025

-

WHO BETRAYED PROPHET ISA (JESUS)?26.11.2025