(1).jpg)

DO NOT BE ARROGANT, MY SULTAN, FOR THERE IS A GREATER ONE THAN YOU—ALLAH!

The weekly outings of Ottoman sultans to the mosque for Friday prayers were among the most magnificent ceremonies of imperial life. Known as the Cuma Selamlığı or Selamlık Resm-i Âlisi in Turkish, these ceremonies were strictly governed by protocol rules in every aspect and held great political significance.

They ensured the ruler's close connection with his subjects and provided the people an opportunity to present their requests and grievances to the sultan. It was a sign that the ruler was alive and that both the Sharia and the established order were upheld.

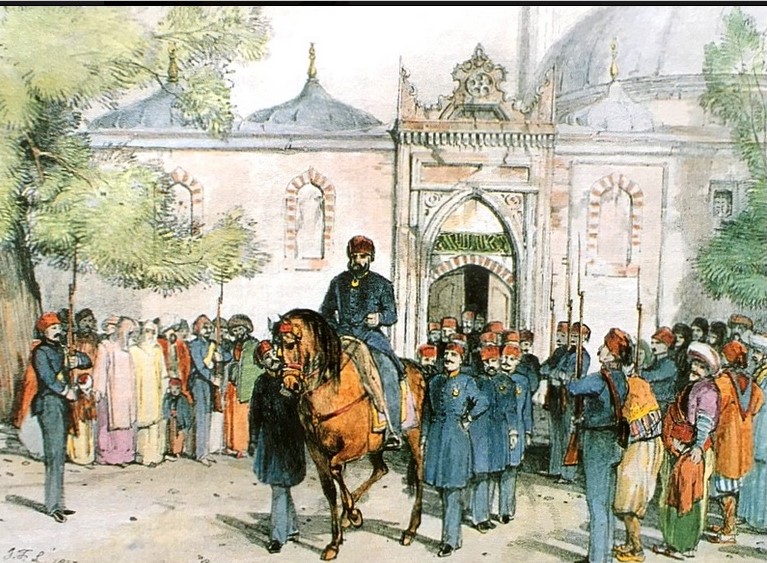

The sultan would ride to the mosque on horseback or in his carriage, passing through soldiers of the ceremonial units lined up on either side. Meanwhile, crowds would gather in the streets, eager to catch a glimpse of "the most majestic ruler of the time." It was not only a spectacle for the common people but also a remarkable event for foreigners present in the empire.

Sultan Mahmud I, despite being too ill to ride a horse, disregarded his doctors' warnings and insisted on attending the Friday procession. "If the people do not see the sultan at Friday prayers, they become uneasy," he said. Staying true to the characteristic traits of his dynasty, he made a great sacrifice to fulfill both his religious and political duty. After the prayer, he struggled to mount his horse with the help of his silahtar ağa (sword-bearer). As he entered the palace gates, he passed away in the arms of his attendants.

A Turning Point for the Caliphate?

Records of ceremonial protocol and chronicles frequently mention the Friday processions. There is detailed information about those held during Sultan Abdulhamid II’s reign.

Previous Muslim rulers had always attended Friday prayers, but none had done so with the grandeur of the Ottoman sultans. In the Anatolian Seljuk era, an official known as emîr-i mahfil was responsible for organizing the sultan’s Friday prayer ceremonies.

Ali Seydi Armaner, in his book Teşrifat ve Teşkilat-ı Kadîmemiz (Our Old Ceremonial and Institutional Traditions), states: “Previously, Friday prayers had no official aspect. The sultan would usually pray at the palace mosque or one of the imperial mosques, accompanied by some viziers and palace officials. After the caliphate passed to the Ottomans, Friday prayers gained official status.” However, considering that Sultan Selim performed a Friday procession in Tabriz, this tradition seems to date back even earlier.

When sultans were on military campaigns, the Friday procession was held if their headquarters were in a large city. Sultan Selim conducted it in Tabriz, Sultan Suleiman I in Buda, and Sultan Murad IV in Yerevan and Baghdad. If the sultan was in Edirne, the Friday procession was held at the Selimiye Mosque.

During times of upheaval, such as revolutions, this ceremony was not held. However, after a coup, the first act of Sultan Mustafa IV, who ascended the throne on a Friday, was to participate in the procession.

First Task: The Turban Procession

In earlier times, Friday processions were conducted with great pomp in major mosques such as Hagia Sophia, Fatih, Bayezid, and Sultan Ahmed (The Blue Mosque). However, when Sultan Mehmed IV ascended the throne at the age of seven, Istanbul was still experiencing the aftereffects of a coup. As a result, the procession became simpler, consisting only of the çavuş (sergeants) and peyk (couriers) dressed in striking garments.

The çavuşbaşı (chief sergeant) would go to the mosque in advance carrying the sultan’s turban, a ritual known as the sarık alayı (turban procession), which indicated where the sultan would perform his prayers. On the day of the procession, the roads were sanded and smoothed. Janissaries lined both sides of the mosque path, through which the sultan rode his horse.

On either side of the sultan’s horse walked the solaklar, an elite Janissary guard unit. These guards were highly skilled in using their left hands to counter threats from that side.

Sultans attended the Friday processions on horseback. At the palace’s middle gate, the silahtar (sword-bearer), çuhadar (robe-bearer), and kapı ağası (palace gatekeeper) mounted their horses to follow the sultan. The grand vizier would wait on horseback behind the gate and salute the sultan from the left. Zülüflü ağalar (officers with sidelocks) would also join the processions. The rikâbdar (stirrup-holder) would stand at the sultan’s left stirrup, while the çuhadar ağa would stand at the right. As they exited the outer gate, the çavuş would chant praises. When the sultan mounted or dismounted his horse, a prayer-officer would recite supplications, to which the others responded, “Hoo!”

At the mosque courtyard, the yeniçeri ağası (commander of the Janissaries) and the mosque’s trustee would greet the sultan. The ağa would remove the sultan’s boots and put on his slippers. If it was his first time performing this duty, he would be rewarded with a diamond-encrusted dagger. Then, the grand vizier and the yeniçeri ağası would escort the sultan to the imperial prayer lodge (hünkâr mahfili).

The mosque trustee would carry a censer filled with fragrant incense. The sultan would perform the Friday prayers in a designated area within the mosque. Since the martyrdom of Caliph Uthman, all Muslim rulers had prayed in such protected spaces. The yeniçeri ağası would inspect the mahfil in advance, lay the sultan’s prayer rug, and after the prayers, assist in putting on his boots and walk before his horse.

During the return processions, high-ranking officials would approach the sultan’s horse to present their reports and petitions.

The procession During the Hamidian Era

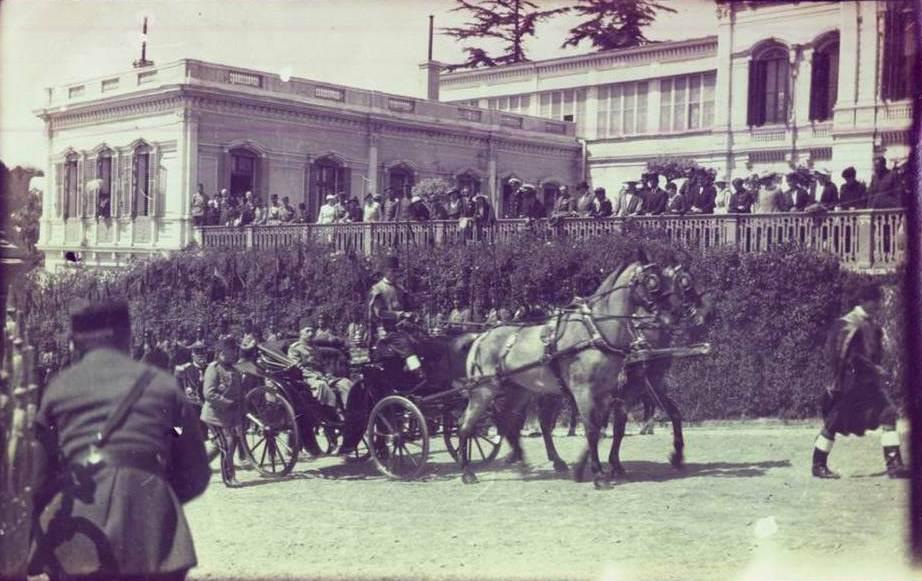

On December 15, 1876, Sultan Abdulhamid II, suffering from a toothache and swollen face, attended the procession at Hagia Sophia in a carriage to shield himself from the wind. From then on, he always attended in a carriage.

During ceremonies such as Bayram Selamlığı (festival procession) and the Friday procession, when the sultan passed by, the audience continuously bowed, and he reciprocated their greetings.

Sultan Abdulhamid II performed processions at different mosques and often took short or long excursions afterward, either on land or by sea. The farthest mosque he visited was Eyüp Sultan.

The Bayram Alayı (festival procession) followed the same format as the Friday procession, but the ceremonies in which the sultan was girded with the sword were even more magnificent. In Friday processions, four state carriages were used, while six were used during festival and sword-girding ceremonies.

Many officials from military, civil, and religious institutions participated. Several battalions from different military branches also joined, and after the prayer, a parade was held in front of the sultan at the mosque’s entrance.

This military spectacle revived the city’s energy after a week of stillness, filling and emptying the streets along the procession’s route.

In the Friday processions, all the princes, some aides-de-camp, riflemen, and the hünkâr çavuşları (imperial sergeants) would be present. Since it was not known in advance in which mosque the selamlık would take place, those participating in the ceremony would gather at the Çit Pavilion in Yıldız and wait for the imperial decree determining the location. Once the decree was issued, they would proceed together with the sultan.

"Do Not Be Arrogant, My Sultan!"

The beginning of the ceremony was signaled by the departure of the gidiş müdürü (director of processions and outings responsible for the sultan’s ceremonies and excursions) alone through the palace gate. Following him, the imperial carriage would come into view. At that moment, cheers would erupt, and the Hamidiye March, played by the military band, would be heard.

Around ten imperial attendants would chant the alkış (cheering) in the highest pitch. Wherever the sultan went, they would repeat the same cheers as he stepped out of the carriage. The alkış was as follows:

"May your path be auspicious, may you live long, may your way be open, do not be arrogant in your reign, my sultan, for there is One greater than you—Allah!"

During the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, an additional phrase was included: "May you live a thousand years in your glory and sovereignty." However, during the reign of Sultan Mehmed V, this phrase was no longer recited.

As the sultan entered and exited the mosque, the same ceremony was performed, and along with these chants, the gathered crowd would shout, "Long live our sultan!" creating an uproar. The modern equivalent of applause—clapping—was neither known nor practiced in those times.

During a Friday procession, Sultan Mehmed VI once said to mâbeynci (imperial chamberlain) Ömer Yaver Pasha:

"There is no longer anything to be arrogant about. Silence them. There is no need for such ostentatious displays."

Following this, the tradition was abandoned.

Private Mosque

When Sultan Abdulhamid II left the palace, he would ride in a four-horse imperial carriage, but after the prayer, he would return to the palace in a two-horse carriage. The horses pulling the imperial carriage were bay, while those of the other carriage were white. On the return journey, he would drive the carriage himself. There was no one beside or in front of him, nor was there a coachman.

On his way to the mosque, he would initially have Eğinli Said Pasha sit across from him in the carriage, later Namık Pasha, then Gazi Osman Pasha, and finally Serasker Riza Pasha.

As the Friday procession gained increasing significance and included various ceremonies and parades, it became difficult to conduct them in different districts every Friday. Not every mosque was suitable for these ceremonies. For this reason, a new mosque was needed near the palace, where all these ceremonies could be carried out conveniently. In 1891, the Hamidiye Mosque was built. The claim that the Sultan did this out of fear is untrue.

Prayer Is Not Interrupted for Anyone

Sultan Abdulhamid II performed his prayers in the imperial prayer lodge (hünkâr mahfili) of the mosque, which was large enough to accommodate three rows of worshippers. He prayed in the backmost row, in a corner by the wall. Before the prayer, he would occasionally sit for a while in the screened section, which allowed him to observe the congregation arriving at the mosque.

During the Sunnah prayers, those in the mahfil would follow the Sultan. No one would start the Sunnah prayer before him. However, some would finish before him, while others would lag behind. On one occasion, the Sultan finished his prayer and suddenly stood up. However, among the congregation, İzzet Pasha had not yet finished his prayer. Seeing that the Sultan had risen, he immediately interrupted his prayer and stood up out of respect. The Sultan warned him, saying, "Prayer is not to be interrupted for anyone."

After the prayer, the Sultan would sit in an armchair placed by the stove and window in the mahfil. At that time, the director of protocol would enter and present the names of notable individuals who had come to the mosque and the designated viewing areas for the Friday procession.

The Sultan would receive and honor some of these individuals while standing in the mahfil. Mustafa Kemal Pasha was received and bid farewell by Sultan Mehmed VI in the mahfil after the Friday prayer before his official departure to Anatolia.

The person Sultan Abdulhamid II met with the most after prayer and always showed great respect to was Sheikh al-Islam Cemaleddin Efendi. On July 21, 1905, terrorists had planted a time bomb in the Sultan’s carriage, calculating his every move. However, due to an unusually long conversation between the Sultan, the Sheikh al-Islam, and the mosque imam (regarding the leaking eaves of the mosque), the bomb exploded before the Sultan reached the carriage, thus saving his life. Previously, on December 17, 1791, a Maghrebi madman had attempted to assassinate Sultan Selim III by throwing lead balls at him in the Hagia Sophia Mosque.

News for the Newspapers

Half an hour before the prayer, the carriages of palace and government ladies who wished to watch the procession would be admitted to the courtyard under police supervision. The shafts of their carriage horses would be removed, and the horses would be taken to the back of the mosque.

Once preparations were complete, the director of protocol would inform the Sultan. The Sultan would exit through the harem gate and board his carriage. As the carriage left the harem gate, the princes-in-law and palace attendants would salute the Sultan and follow his carriage.

Across from the Great Mabeyn Hall, all the aides-de-camp would line up and join the procession after saluting. As the carriage exited through the imperial gate, the alert bugle would sound, and the troops would stand at attention. Not a soul would stir. Meanwhile, the call to prayer would be recited.

After the prayer, the Sultan would order the soldiers to return to their units and then return to the palace. The Friday procession would be reported in the Saturday newspapers in an ornate and grandiose language.

A Double?

Sultan Abdulhamid II suffered from severe illnesses such as bronchitis, pneumonia, and kidney pain on several occasions. It is said that during such times, fearing that his absence from the Friday procession might lead to speculation or misunderstandings, he would have his trusted milk brother, Chief Wardrobe Officer İsmet Bey, stand in for him during the ceremonies.

Sultan Mehmed V missed the Friday procession once due to measles and twice due to bladder surgery. He would tour all the suitable mosques in Istanbul for the procession. For instance, he would attend prayers at mosques such as Sultan Selim, Fatih, Sultan Ahmed, Bayezid, Ortaköy-Mecidiye, and Beylerbeyi.

After the procession, the official uniforms would be changed, carriages would be boarded, and a light parade would be taken for leisure. Destinations included Balmumcu Farm, Ihlamur and Zincirlikuyu pavilions, and occasionally Beylerbeyi Palace by imperial barge.

On one occasion, the journey extended to Ayazağa and Kağıthane pavilions, which held many memories of his youth. This effort was endured as a means of escaping the confined palace life for a few hours. However, the person most exhausted by this was undoubtedly the director of protocol.

If Only We Could See the Sultan

The Minister of Religious Endowments, Minister of Public Security, Imperial Guard Marshal, Beşiktaş Governor, and other high-ranking officers were required to be present at the Friday procession. The Minister of War and the Minister of the Navy, along with all the highest-ranking aides-de-camp, were also required to attend. The Grand Vizier and other ministers were not obligated to be present, but the Sheikh al-Islam was always in attendance.

Although the public was allowed to enter the mosque to perform the Friday prayer, reaching Yıldız from Beşiktaş required significant effort and numerous security checks.

Hundreds of plainclothes and uniformed officers would roam among the crowd, observing and investigating people. Those who managed to pass through these checks and reach the mosque entrance would undergo a full-body inspection before entering.

The spectators stood at a distance. Since the use of binoculars or other visual aids was not permitted, they were unable to catch a glimpse of the Sultan. Pilgrims from Russia and other regions, visiting for Hajj, especially wished to see the Sultan. Although the police tried to prevent them, they would sometimes climb nearby trees to catch a glimpse.

Was He Really Unassailable?

A closed area on a platform in front of the Mabeyn Chamber was allocated for foreign ambassadors. They were hosted there with great hospitality, served coffee and cigarettes. The Sultan was particularly attentive to treating the ambassadors well.

For foreigners visiting at the recommendation of embassies, a spacious covered amphitheater-like area was allocated across from the clock tower. As the Sultan passed by, he would greet and show courtesy to them, and he would also send his protocol officer, Şeker Ahmet Pasha, to convey his greetings and royal satisfaction.

Foreign spectators were subject to strict control and questioning. They were absolutely not allowed to carry cameras, handbags, canes, or umbrellas.

During her stay in Istanbul, the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt, while watching the Sultan’s procession from one of these tribunes, remarked to those around her, "They say Abdulhamid cannot be shot. But from here, he could very well be shot with a pistol."

Somehow, this remark reached the Sultan’s ears, leading him to have the closed tribunes removed so that officials could better monitor the spectators. From then on, foreigners watched the ceremony from open tribunes.

The foreigners in Istanbul at that time vividly described these processions they witnessed in their memoirs. One such observer was the wife of Max Müller, a British Member of Parliament, who visited her sons at the British embassy in 1893.

Are They Executioners?

The imperial military units participating in the Friday processions gathered at Bayezid Square. Then, upon the signal of the bugle call, they marched forward with the clatter of weapons and the neighing of horses. The processions included the soldiers of the 1st Brigade, 1st Sharpshooter Regiment, the tall soldiers of the 1st Plevne Battalion, the other battalion of the 1st Brigade, the fire brigade battalion, the Ertuğrul Cavalry Regiment, the cavalry band regiment, and the light cavalry regiment, all moving in sequence.

The passage of these troops was truly awe-inspiring. At the front of the battalion marched water carriers in leather uniforms, their rifles slung across their bodies. Behind them followed a row of large, burly axemen. These men wore tall fezzes and leather breastplates extending from the neck down to the knees, resembling a blacksmith’s apron. They had thick beards, their rifles slung across their chests, and they carried large, sharp, and polished axes resting on their right shoulders with the blade facing upward.

According to legend, when the German Kaiser first visited Istanbul, the Empress, upon seeing these men, became frightened and asked, "Are they executioners?" Upon hearing this, Sultan Abdulhamid II was deeply saddened. To prevent foreigners from misunderstanding the situation, he removed these soldiers from the parade.

The Military Band

Every regiment had its own band, and each battalion had fully equipped bugle and drum corps. Since these musicians had spent a long time in service, they played their instruments with skill and precision.

The procession set off from Bayezid Square, exiting through the Mercan Gate of the Bab-ı Seraskeri (now the entrance to the university), proceeding down Mercan Slope, through Sultanhamam, Yeni Cami, the Bridge, Galata, and Tophane before arriving in Beşiktaş. Along the way, crowds gathered on the streets to watch.

In front of the Kapıiçi Police Station, the buglers fell silent, and the band played marches. A small artillery detachment emerged from the Tophane Military Headquarters to salute the passing troops.

At the same time, a battalion of navy riflemen and a company of naval troops, accompanied by the naval band, marched from the Imperial Dockyard through Şişhane and the Grand Avenue (Cadde-i Kebir) to Maçka before descending to Beşiktaş. Among the public, this naval band was particularly renowned.

In Beşiktaş, the troops gathered in front of Sinanpaşa Mosque, stacking their weapons and awaiting the order to march. To avoid causing hardship to the soldiers in extreme weather, the ceremony was kept brief.

At the top of the steep slope leading to the palace and near the Sultan’s Gate, a rifle company from the Imperial Guard, the Söğütlü (Ertuğrul) Company, and two companies from the Yıldız Battalion were positioned.

Below the Sultan’s Gate stood the Plevne Battalion, while a battalion from the turbaned Arab Zouave Regiment lined up along Beşiktaş Street. Opposite the mosque, a battalion from the fez-wearing Albanian Zouave Regiment took position, followed by artillery, engineering, and logistics units.

The Final Authority

The Friday Procession is one of the most significant yet overlooked aspects of Ottoman history. When the Sultan exited the mosque after Friday prayers, petitions from the public were collected by a special official known as the "secretary of petitions" and presented to the Sultan.

After reviewing these petitions, the Sultan would refer them to the relevant authorities for necessary action, with follow-ups to ensure results. Generally, these petitions were forwarded to the Grand Vizier for processing. The Ottoman archives are filled with such petitions and the corresponding imperial decrees addressing them.

Because of his dedication to staying informed about everything, Sultan Abdulhamid II took this tradition very seriously. During the Friday Processions, people would hold up their petitions, and a uniformed official with a satchel would collect them and present them to the Sultan. The Sultan assigned Gazi Osman Pasha to examine these petitions and even provided him with a special office within the palace for this purpose.

The tradition of presenting petitions to the Sultan continued until the abolition of the Caliphate. It can be considered a precursor to modern citizens submitting petitions to the President or Parliament.

The Silence of Death

The last Friday procession attended by a Sultan took place on November 10, 1922, in eerie silence, without music. On November 17, the procession was not held—because the Sultan had gone into exile. The first procession of the new Caliph, Abdulmajid II, took place in Fatih. His route, entourage, and attire were all dictated by Ankara, and in the carriage beside him sat Refet Bele, Ankara’s commissioner in Istanbul. The last Caliph was greeted and sent off with the National Anthem of the republic.

The final Friday procession occurred on February 29, 1924. Münevver Ayaşlı recalls: "I saw Caliph Abdulmajid Efendi’s departure for Dolmabahçe Mosque. A few princes, a few journalists, and at most thirty curious onlookers had gathered. No classical writer, not even the famous Shakespeare, could have written or staged the tragedy of this scene.

I can never forget the expression on the Caliph’s face—somber, resolute, and resentful... Everyone was bewildered, yet they did not fully grasp the gravity of the situation. There was a strange belief among them that this could never truly be happening. But the most poignant and dramatic moment of all was when an elderly woman from the common people, unaware of everything, threw a petition into the Caliph’s carriage, as was customary. In today’s terms, a woman from the nation submitted a petition to the Caliph. A Caliph who had already lost all his rights—even his citizenship!"

Three days later, the Caliph and the entire Ottoman dynasty were stripped of their citizenship and exiled abroad by the Ankara government.

Önceki Yazılar

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025