(1).jpg)

WHY AND HOW WAS THE TURKISH REPUBLIC PROCLAIMED?

The Ankara government had already functioned as a republic, at least since the abolition of the sultanate. So, what does the proclamation of the Republic on October 29, 1923, signify?

After four years of chaos during the Great War, known as the World War I, the Ottomans encountered an unprecedented and unexpected calamity. The capital, Istanbul, was occupied. At the time, the Ottoman regime was a crowned democracy. During this period of ruin, Sultan Mehmed VI dissolved the parliament, which he held responsible for these events. Leading the Young Turks (the members of the Committee of Union and Progress) fled abroad, intending to return when the conditions were favorable. Some of those who stayed behind moved to Anatolia, while others were exiled to Malta by the British.

President Mustafa Kemal and Prime Minister İsmet

Who Was the Head of State?

Mustafa Kemal Pasha, who was sent to Anatolia with the title of army inspector to organize resistance movements and strengthen Istanbul’s position against the Allies, established a provisional government in Ankara. Elections were held, and the Ottoman Parliament reconvened in Istanbul in 1920. Although Mustafa Kemal Pasha was elected as a deputy, he did not attend, as if foreseeing what lay ahead. He wanted the parliament to be in Ankara and under his control. Even so, most deputies were individuals supported by Ankara. When these deputies adopted the Misak-ı Milli (National Pact), which defined the country's borders as prompted by Ankara, the British dissolved the parliament. The deputies relocated to Ankara, and the new parliament convened there on April 23, 1920. Mustafa Kemal achieved his aim. Ankara had done everything possible to ensure the dissolution of the parliament in Istanbul.

Within the framework of a wait-and-see policy, the British, noticing Ankara's rising prominence, released the Malta exiles in exchange for a few British prisoners. These individuals joined Ankara. Although the British could have prevented the parliament from convening in Ankara, they chose not to. Thus, a new Young Turk movement emerged in Ankara. The British had already written off the sultanate. England, which ruled a quarter of the world and had a significant Muslim population, had concentrated its 19th-century policies on diminishing and abolishing the power of the caliphate. As Ankara gained political prominence, London openly began to lend its support.

President Mustafa Kemal Pasha leaving the parliament in Ankara

During this period, the regime in Ankara was a parliamentary system. The cabinet and judiciary were directly subordinate to the parliament. Mustafa Kemal adopted this system, practiced in Switzerland, within the context of the prevailing conditions. However, he expanded its authority-restricting principles by taking advantage of various opportunities. When the sultanate was abolished, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, as both commander-in-chief and head of the parliament, was the most powerful figure. While engaging in dialogue with the French, Italians, Russians, and British to narrow the front, he also succeeded in neutralizing opposition groups whenever the opportunity arose.

With the abolition of the sultanate on November 1, 1922, the sultanate and the caliphate were separated, and a symbolic caliphate without executive powers was established. Crown Prince Abdulmejid II was appointed to this position by the parliament in Ankara. Sultan Mehmed VI, accused of treason and forced to leave the country, declared in a proclamation that this law, which was tantamount to a constitutional amendment, could not take effect without the sultan's approval, making it unconstitutional. He also stated that the sultanate and caliphate could not be separated and criticized his cousin for accepting such a position. By now, Ankara was the sole interlocutor of Britain and its allies, participating in peace negotiations independently. However, in the eyes of the people, and even the deputies, the head of state was still Caliph Abdulmejid II in Istanbul. According to Islamic-Ottoman constitutional law, the caliph was not only a spiritual leader but also the head of state.

The Pashas’ Conspiracy

Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s growing authority caused some of his colleagues, dissatisfied with the situation, to seek alternatives. They wanted Mustafa Kemal to be a president above politics. However, Mustafa Kemal, being a shrewd politician, knew that being "above politics" meant staying out of political affairs. Moreover, whoever crowned someone could dethrone them tomorrow. Without a strong political base or control over the parliament and military, one's future would be uncertain. No genuine political ambition could accept such a formula. Mustafa Kemal then devised a political strategy against them. He claimed that holding two positions simultaneously was problematic and demanded that his colleagues, who were both commanders and deputies, resign from one of their roles.

While some left the military, Kazım (Karabekir), Ali Fuad (Cebesoy), and Cevad (Çobanlı) Pashas chose to remain army commanders, which led Mustafa Kemal to suspect a military conspiracy against him. When these individuals later resigned their commands and returned to parliament, Mustafa Kemal interpreted this as a political conspiracy. For the first time, candidates opposing Mustafa Kemal were elected ministers in the parliament, which had previously always chosen his nominees. The election of Rauf and Sabit Bey from the opposition particularly infuriated Mustafa Kemal. Rıza Nur remarked that the opposition, believing Mustafa Kemal was leaning toward dictatorship, attempted to challenge him through legitimate means but made a mistake by choosing parliament over the military.

The opposition gained increasing strength. Elections were held in 1923, and the new parliament was formed with deputies loyal to Mustafa Kemal, excluding dissenters from the first parliament. Although the new parliament was republican in character, dissenting voices still emerged. The visit of Rauf (Orbay), Refet (Bele), and Adnan (Adıvar) Beys to the caliph on October 19 was the final straw.

In his "Nutuk" (The Speech), Mustafa Kemal described how disturbed he was by this event. To establish a government that would align with him, he planned a crisis. He first obtained the resignation of Prime Minister Fethi Bey, who was already under heavy criticism, and of all ministers except Fevzi Pasha. On the night of October 28, while prominent opposition figures were out of town, he convened a meeting at Çankaya with seven loyalists. He instructed them to deliver speeches the next day that would obstruct the formation of a government. After the meeting dispersed, İsmet Pasha remained. Mustafa Kemal dictated to him the proposal for the proclamation of the republic.

Authoritarianism

On the morning of October 29, the assembly convened, unaware of the developments. However, no government list could be prepared that would garner majority support. Everyone approached for the role declined, as they had been pre-warned. (At the time, ministers were chosen by the assembly.) As a last resort, the assembly turned to Mustafa Kemal. He submitted his proposed law to the assembly. According to it, the regime would be officially named a republic; the authority to select the prime minister would belong to the president, while the authority to select ministers would rest with the prime minister.

The assembly approved the proposal that night with a narrow vote: of 328 members, only 158 voted in favor. The requirement that constitutional amendments be passed with a two-thirds majority was not applied in this instance either. According to Yakub Kadri, the concern of the deputies was not with the republic but with the move toward authoritarianism. The press was surprised by the hasty proclamation of the republic. However, this move not only suppressed opposition but also served as a warning to the caliph. A few months later, the caliphate would be completely abolished, securing the regime.

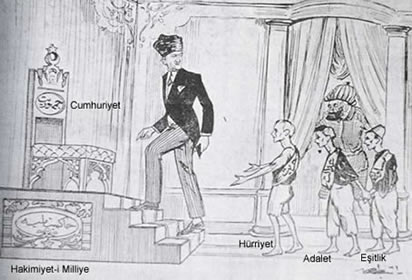

A cartoon about the proclamation of the republic in the satirical magazine "Karagöz"

When Mustafa Kemal was elected president, exceptional powers were granted to him. He now held the highest authority in the country, as head of state, government, parliament, and the party—a position of power that even sultans might envy. While it is often said that the republican system had always been in his vision, this claim is questionable when considering Mustafa Kemal’s earlier attempts, such as becoming the Minister of War or the son-in-law of the sultan, like Enver Pasha. Moreover, the system proclaimed in 1923 cannot be described as a democratic one. Except for Sultan Abdulhamid II, the role of the Ottoman sultans in the last century does not go beyond that of supra-political heads of state in the modern world. By contrast, republican governments always possessed unlimited power and, with their lavish lifestyles, often eclipsed the sultans.

When a monarchy is abolished, a republic is automatically established in its place. In Türkiye, the period between the abolition of the sultanate on November 1, 1922, and the proclamation of the republic on October 29, 1923, was effectively an unnamed republic but also a transitional phase. On October 29, 1923, both the regime’s name was formalized, and one-man rule was codified.

The October 30, 1923, issue of "Hakimiyet-i Milliye" newspaper announcing the proclamation of the republic

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025

-

WHO BETRAYED PROPHET ISA (JESUS)?26.11.2025