“WHAT'S THE POINT OF LIVING?” OTTOMAN PRISONERS IN POW CAMPS

Thousands of Ottoman prisoners in captivity camps during the First World War suffered greatly, even under good conditions, due to homesickness, losing both their mental and physical health.

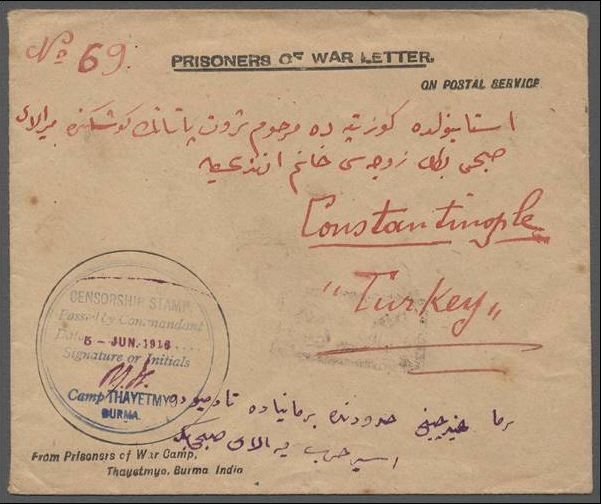

During the First World War, 202,000 Ottoman prisoners were held for several years in British, French, Russian, and Romanian camps. Except for the Russian and Romanian camps, the conditions were not bad. The most significant issue in all camps was the lack of communication with their homeland. Letters did not arrive or were delayed. Some soldiers had no one to write to or receive letters from. Incoming and outgoing letters were censored. The lack of Turkish books and the provision of beef instead of mutton were common problems. Complaints varied by location. In some camps (Corsica), the absence of tobacco and socks was an issue; in others (Egypt), prisoners complained about wanting boots instead of the heelless leather shoes provided; and in some camps (Cyprus), the bread made from coarse barley was a matter of grievance. Extreme heat or cold, continuous rain, and infestations were common complaints in some camps. My grandfather used to recount that he escaped from a Siberian camp because he grew weary of eating horse meat.

The Camp’s Chicken Coop

Most Ottoman officers knew French, but interpreters were present among the prisoners or civilians in the camps. Officers, and sometimes soldiers, were paid salaries. Charitable organizations collected and distributed money for the soldiers. Receiving money from their homeland was also allowed. Clothing, including fezzes, and undergarments were provided. As the clothes were fumigated weekly, lice and fleas were minimal. Camps had mosques and imams, and religious days were celebrated.

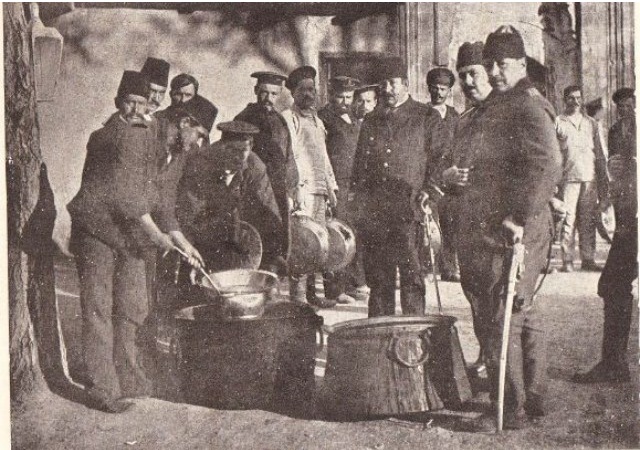

Doctors and medical personnel working in infirmaries were paid, thus enjoying better conditions. Skilled prisoners such as barbers, carpenters, shoemakers, and tailors could practice their trades and earn money. Others formed labor battalions and were employed in tasks like cleaning the area or cutting trees. Some jobs, like gardening or cleaning around the camp, were paid. In some camps, no work was required at all. The camps had disinfected latrines and showers, cleaned daily. Soap and water were plentiful, and water was treated. Religious dietary restrictions were observed in meals. Those with money could purchase available items from the canteen. Some prisoners grew fruits and vegetables or raised chickens in the camp. My grandfather, knowing how to cook, used to say he didn’t suffer much in the camp.

Boredom was a major problem. Prisoners tried to overcome it by learning languages, reading books, publishing handwritten newspapers, or forming musical bands. In some camps, officers were permitted to visit nearby towns. Some prisoners made and sold handmade goods, such as bead necklaces, bags, cigarette holders, and prayer beads. Sports, especially wrestling, were favorite pastimes. Officers who knew foreign languages translated foreign books into Turkish for others to benefit from. In Egypt, prisoners were once allowed to meet relatives in another POW camp. Tensions occasionally arose between Young Turk prisoners and opposition members, as well as between Turks and Arabs.

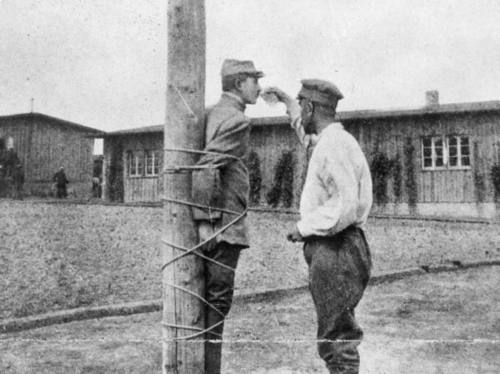

Blind Prisoners

Sick prisoners were treated in the camp infirmary and sent to hospitals if necessary. Dentists were called from nearby towns when needed. Deceased prisoners were buried in special cemeteries after religious and military ceremonies attended by camp officers. Captivity itself was a source of distress. Especially in India, prisoners displayed symptoms of a psychological disorder known as "barbed-wire disease," characterized by quick agitation, irritability, hypersensitivity, introversion, and in extreme cases, suicide or murder. They told doctors, “I’m tired of watching the barbed wire. What’s the point of living?” Other than this, there were no significant illnesses beyond the usual in POW camps. Most soldiers captured on the Egyptian front suffered from conjunctivitis (eye inflammation) caused by sandstorms, as they weren’t provided desert goggles during the Canal Campaign. In disinfectant pools soldiers were immersed in upon arrival, medicated solutions sometimes entered their eyes.

It was said that some Armenian doctors in the infirmaries, driven by a desire for revenge over the deportations, deliberately applied incorrect treatments, causing 15,000 soldiers to lose their eyesight. Although this incident was investigated upon Ankara’s request, it was not substantiated. According to Turkish official records, only about 310 soldiers who returned from captivity were blind.

The conditions for prisoners in Romania were harsh; the places where they were held and the food they were given were poor. They were forced to work in heavy labor. However, during the war, the situation of the Romanian people and army was not much different. The prisoners complained about their watches and money being confiscated.

The number of prisoners in Russia was high, and their conditions were extremely severe. The weather was cold, the distances vast, transportation arduous, and resources scarce. Due to the revolution, there was chaos in society. There were many pests, the cold was relentless, the beds were insufficient, and the camps were far from populated areas. Contagious diseases were widespread, and 20% of the prisoners perished.

Since there was much to recount, most published memoirs of captivity were written by prisoners in Russia. Almost all of the captive officers kept diaries. The Russians, thinking that the situation could turn against them at any moment, did not treat the prisoners poorly. Furthermore, the Bolsheviks did not refrain from carrying out propaganda among these soldiers.

The Real Captivity Was Upon Return

The protagonist of Reşat Nuri Güntekin’s novel “Son Sığınak” (The Last Shelter) was captured during the Canal Campaign and spent time in the Zekazik prisoner-of-war camp. Occasionally, his mind would wander back to the bittersweet memories of those times:

"Even while waiting to be taken to execution with my cellmate at the bottom of the well in the Zekazik camp, I didn’t neglect to shave my beard with a rusty razor blade. The British locked us, along with a few others, in a well for 15 days. We passed the time by telling stories to each other. In the camp, we built sets and staged plays. Even the British officers who occasionally came to watch were impressed. A few humorous memories remain from this camp theater. For instance, we gave the role of a girl playing the violin to her lover on the street, standing by a window, to a band soldier who looked as pretty as a girl when dressed in women's clothing. This theater in the Egyptian camp became a refuge for us. We adorned this stage with great care. We even took it to other locations and never minded its comical aspects."

For prisoners of war, the most bitter part was the uncertain fate awaiting them upon their return. Many found their families dead or exiled. Their homes were destroyed, and their livelihoods ruined. Finding a job was out of the question; they waited in despair for days just to secure a piece of bread. As with other places around the world, the treatment their government and society reserved for their heroes was no different. Reşat Nuri has his protagonist recount:

“There was something I occasionally missed about my life in Egypt. In the camp, surrounded by barbed wire in the middle of the desert and guarded by colonial-hatted British sentries, we felt an intense will to live. Our minds churned out dreams like printing presses. Strangely, the most hopeful time for us was during the days the British confined us to that well. Truth be told, the Zekazik camp, for us, became what Istanbul was during the Armistice years. There was nowhere left to escape to. It was as if I had no one in Istanbul. My home had long since fallen apart. If there were a few distant relatives or acquaintances scattered here and there, I had to act as if I didn’t know them. With my old clothes and the unhealed wound on my leg, humiliation radiated from every part of me. No matter what I did, I couldn’t prevent people from assuming I was looking for something or waiting for help.

One day, a friend from the camp whom I ran into on Çakmakçılar Slope said to me: ‘You’ll remember the day we walked eight or ten hours barefoot under the scorching desert sun. Now, my soles burn even more when I go to the Ministry of War or other places to ask for work.’ Eventually, a Jewish friend from Galatasaray found me a job. It was in a shop in Tahtakale, crammed with barrels and cans of paint stacked on top of each other. I worked in a glass-enclosed corner that barely fit my desk and chair, lit by a bulb all day. I was like a clerk, keeping records. Thanks to the little English I learned in Egypt, I wrote letters in French and English.”

Önceki Yazılar

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025