GALLOPING THROUGH HISTORY: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE'S POSTAL COURIERS

One of the factors that kept the Ottomans in power across three continents for six centuries was their fast and organized communication system. Postal couriers tirelessly delivered messages from one end of the empire to the other, changing horses at way stations along the route; if no horses were available, they could even take a horse from the governor's stable.

Throughout history, people have communicated using carrier pigeons or by lighting fires and sending smoke signals from one castle to another, or by shooting arrows. The Ottomans also utilized these methods. However, official couriers, known as postal couriers, played the most crucial role in communication. Turkish expressions like "Yaya kaldın tatar ağası!" (You’re left on foot, chief courier!), "Tatarın gidişini beğenmedim!" (I didn’t like the way the courier went!), and "Atı alan Üsküdar’ı geçti!" (The one who got the horse has crossed to Üsküdar!) originate from these times.

No Free Rides!

During the Ottoman Empire, way stations similar to fortress inns were built along main roads. These were established at the end of a day's journey (approximately 35 km) for horse riders or walkers. There were waqf inns at these stations where travelers could stay overnight; their horses would be fed, and they would continue their journey the next day. If there was no waqf inn at the station, civilians who built and operated the station were exempt from taxes and could receive allocations if necessary. The goods needed by the army during a campaign were also stored here. Over time, these way stations became marketplaces where local people brought and sold their goods and produce. Eventually, villages and towns formed around these stations. At the way stations, there were officials appointed by the state, such as the way station superintendent (menzilci), stable caretaker, groom, servant, driver, cook, and paid workers from the local population. The state paid for the horses and provisions taken by the official couriers.

Sleeping on the Horse

When the army set out on a campaign, they would stay at these way stations if necessary. Postal couriers delivering messages and letters from one place to another would change their horses at these stations and continue their journey quickly. They wouldn't even dismount while changing horses. They rode day and night, ate on horseback, and slept on horseback. This made it possible to send messages to the farthest corners of the empire in a short time. If postal couriers couldn't find a horse at the way station, they had the authority to take a horse from the governor's stable. The Ottomans developed this system, which had existed since the Seljuk period. Postal couriers were important figures who delivered messages from Hungary to Istanbul, and from there to the coasts of the Indian Ocean, Algeria, and Yemen, ensuring communication between armies. During the reign of Sultan Suleiman I, the Courier Regulation was issued.

The Best Travel Companion

In the Ottoman Empire, postal couriers (posta tatarı in Turkish) were honest, trustworthy, resilient, and quick individuals who could travel quickly. It is said that they were initially chosen from among those of Tatar origin, hence their name. Tatars are a people skilled in horsemanship. There were 300 couriers in Istanbul and 50 couriers under the command of each governor. The couriers were organized under the name of the "Courier Corps" (Tataran Ocağı in Turkish). There was strict discipline among them. Their leader was called the chief courier (baştatar or tatar ağası in Turkish). However, since they were respected and indispensable individuals, all of the couriers were addressed as the chief courier by everyone.

When viziers and governors set out on campaigns, the postal couriers followed them. The witty ones among them entertained the commander and travel companions along the way with humorous conversations, strange stories, and anecdotes, making the journey's hardships more bearable. Traveling with a postal courier was a rare opportunity. There were also couriers who guided travelers. Since they were not in a hurry, they engaged in small-scale trade and could stay at home longer.

Reaching Baghdad in Two Weeks

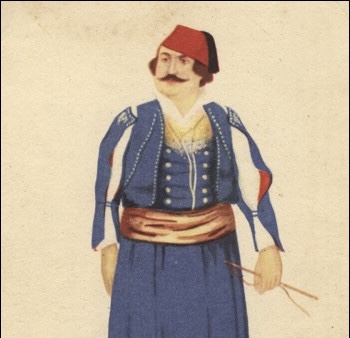

Postal couriers wore practical but majestic clothing and carried fur-lined jackets for use when needed. This allowed them to maintain their health while traveling through different climates. They also carried a belt of a weight that no one else could bear, heavy pistols and yataghans, towels, wraps, handkerchiefs, tobacco pouches, snuff bags, and more, making them almost like a depot of ammunition and supplies. It is known that the couriers could reach Edirne from Istanbul in 2 days, Damascus in 12 days, and Baghdad, 2300 kilometers away, in 14 days.

Crossing mountains, forests, bridgeless streams, and roadless deserts to reach the station was a significant achievement. Welcoming the postal couriers arriving from Rumelia with a load of a hundred horses was an exciting entertainment for Istanbul. Thousands of people eagerly filled the roads, waiting for news from the banks of the Danube. One of the factors that kept the Ottoman Empire in power across three continents for six centuries was their fast and organized communication system.

Evliya Çelebi describes his journey with couriers who carried the news and letters of his patron Melek Ahmed Pasha from Van to Istanbul in 1656. He narrates how eight horsemen from Van traveled northward, changing horses at the way stations and collecting letters from the governors there, and reached Istanbul in 13 days via Malazgirt, Hınıs, Hasankale, Erzincan, Niksar, Ladik, Merzifon, Osmancık, Tosya, Izmit, and Gebze.

Couriers were paid well and also received a percentage from the special letters and policies they carried. If the items they carried were lost, they were compensated by the Corps' fund. However, being a courier was a difficult profession. They spent very little time at home and could only see their families occasionally. Almost all of them were unique individuals. Due to their generosity, they could not accumulate wealth. The hardships they endured also caused them to age and pass away early.

Post Offices

In the early 19th century, a modern postal system began to be established. Posts started being transported by state-employed postal workers using vehicles. Way stations were converted into post offices, and chief couriers were incorporated into the official staff as postal workers. Since postal services in the country were private, there were also foreign post offices. Competition with these foreign offices contributed to the development of the official postal system. At that time, the sender paid the postage fee, and the mail was delivered to the recipient at the post office. Couriers would deliver the mail to remote villages and collect an additional fee from the recipient.

In 1863, postage stamps began to be used, and no fees were charged to the recipient. However, the number of official post offices was limited. In many places, non-official post offices and chief couriers continued the postal service. These were not salaried positions. They would charge the recipient a fee for the items they carried, even for stamped letters. Mail was transported by cars, and later by trains and ships. Couriers would collect the mail from the station or port post office and deliver it to its destination. For further delivery, a chief courier would be involved if necessary.

Postaaa!

The postal transportation between two towns was a sight to see. The chief courier, along with a driver, mounted gendarmes depending on the security situation, and horses specifically for mail transport, would set out. The loads were carried in waterproof leather bags with top flaps. The driver led the way, followed by the loads, and at the rear were the chief courier and the gendarmes. As they passed through places, the couriers would loudly shout "Postaaa!" to inform the public of the mail's arrival. Curious people would gather in front of the postal station. In the southern towns from Damascus, mail was transported by dromedary camels.

The courier system was abolished in 1918. Mail continued to be transported by train, ship, and cars. However, civilian postal workers delivered the mail from stations to distant towns and villages. The job was contracted to the lowest bidder. This system continued well into the Republican era. During my childhood, I knew such postal workers and couriers. For example, there was Mazhar Dayı, may he rest in peace, who always won the postal contract. He would collect the daily mail from the train station and deliver it to a town 70 kilometers away where the train didn't stop. He would also collect outgoing mail from there and deliver it to the train. It was said that as he approached the town, he would spur his horse to create the impression of having ridden at full speed. The incoming mail would then be taken to villages by mounted couriers. If the village headman happened to be in town, they would hand over the village's mail to him. If the distance between two towns was great, the postal workers of the two towns would meet halfway and exchange the mail.

Delivering a Head to the Pasha

Postal couriers also had the task of summoning a person to court or a government office when needed. They would even deliver the heads of executed individuals to Istanbul or provincial centers at a breakneck speed in burlap sacks. The phrase "What's the rush? Are you delivering a head to the Pasha?" originates from this practice.

A Remarkable Turkish Knight

Sir A. Slade, an English admiral who traveled through Anatolia in the early 19th century, recounts: Postal couriers are very handsome, agile individuals. When setting out from Üsküdar, they are examples of life, joy, health, and vigor. Their hair and beard are meticulously groomed, their attire is impeccable. Their cap is tilted slightly forward, and their magnificent clothing, the equipment on their horse, the silver-inlaid pistols at their waist, and their amber-mouthed pipe make them truly a sight to behold as a Turkish knight. However, one should see them upon their return from a long journey. Their own mother would not recognize them. Their face is yellow, burnt, and withered. Their hair and beard are covered in dust and dirt. Their clothes have lost their color due to mud. When their horse stops, they can barely dismount. They are exhausted with pain and fatigue. They no longer have the strength to light their pipe. They can only remount their horse with assistance.

Önceki Yazılar

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025