THE LESSON LEARNED FROM THE "WARNING STONE": THE STORY OF CRIME AND PUNISHMENT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

As in Dostoevsky's famous novel, "punishment" often follows "crime." Punishment is the consequence of a crime. In Arabic, it means "retribution," and when someone says "May Allah punish you," it generally implies a positive intention. In Turkish, it has acquired a negative connotation.

Throughout history, a wide range of punishments, from the mildest to the most severe, from the most humane to the most brutal, have been applied, both related and unrelated to the crime. Due to its negative image in the eyes of society and authority, the offender is often considered undeserving of much sympathy.

In Islamic law, punishment is expected to serve several purposes: to prevent the recurrence of the crime, to compensate for the harm it has caused to the victim and society, and ultimately, to reform the offender.

In this context, in Ottoman history, several types of punishments were applied based on the nature of the crime. First and foremost, there were physical punishments. Indeed, this is the primary form of punishment in Islamic law. Since it produces the same pain in everyone, regardless of race, gender, financial status, or social position, it is considered suitable for the manifestation of justice.

.jpg)

Execution Is Exceptional

"Execution" means carrying out a sentence of death. It refers to the killing of a criminal by court order and by the government. In Sharia law, the death penalty is only applicable for premeditated murder and certain crimes such as highway robbery, adultery of a married person, and apostasy.

In these cases, the likelihood of the death penalty being implemented is very low. The forgiveness of the victim's family or their acceptance of blood money, as well as genuine remorse (repentance) in cases of highway robbery and apostasy, avert execution.

The death penalty can also be imposed as "ta'zeer" (punishment for offenses at the discretion of the judge or ruler of the Islamic state). This is referred to politically as "katl" (killing). For instance, those who habitually commit theft, robbery, or murder, those who extort money from the people, sorcerers, promoters of deviant ideologies, and rebels can be subject to execution.

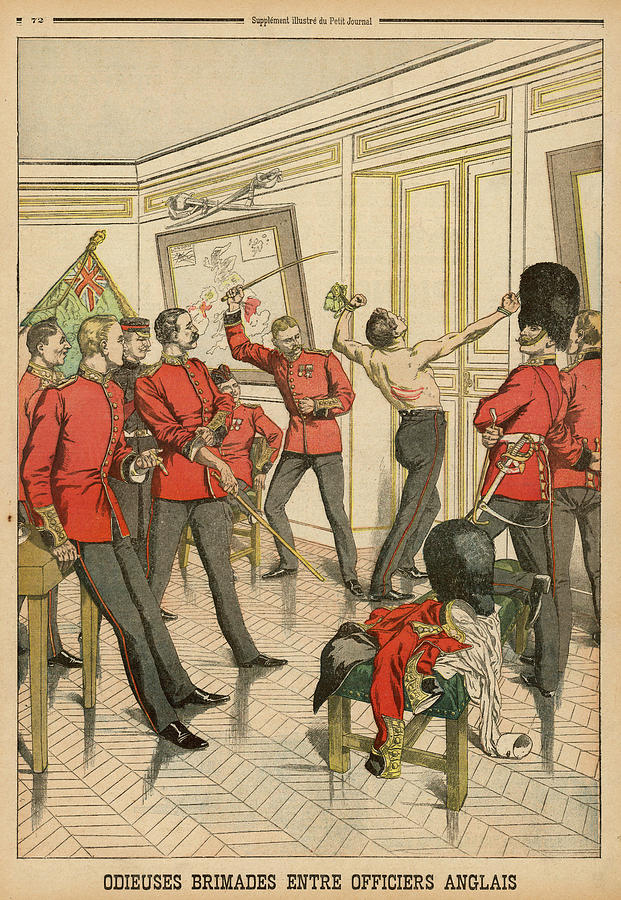

Until the 18th century in Europe, the purpose of punishment was primarily to deter, seek revenge, and publicly shame. There was no proportionality between the crime and punishment, and even for some minor offenses, the death penalty was imposed. It is known that until the end of that century, there were about 200 executions in England and around 215 in France for various crimes. For example, stealing property worth more than 1 shilling could lead to execution. Thanks in part to the efforts of intellectuals, punishments were eventually normalized.

Swift and Painless

Execution is carried out swiftly and painlessly. Hanging as a method of execution is not well regarded. The executed person is buried according to their own religion. Throwing the body into the sea or burning it is not permissible. However, for someone who has murdered their parents and is subsequently killed in retaliation, or for a bandit killed during a confrontation, funeral prayers are not performed.

Retaliation can be carried out against someone who intentionally kills, injures, or mutilates another person, upon the request of the victim. Cutting off the hand is a punishment for theft, but its application is nearly impossible due to the severity of its conditions. It was introduced as a deterrent.

Moreover, even in times of war, cutting off a person's limb or making scars on their face is not permissible; it is considered torture. In contrast, in Europe, even minor crimes were punished with mutilation.

Where Does Flogging Come from?

Punishment by flogging (corporal punishment) is given for crimes such as fornication of a bachelor, false accusations of adultery, drinking wine, and getting drunk, as well as many other offenses.

Typically, it is administered with a branchless (usually hazelnut) wooden stick about one meter long and the thickness of a sparrow's finger in a public place. The stick can only be lifted up to the shoulder. The offender's face, modest areas, and the same parts of the body cannot be struck.

The purpose of the punishment is not to cause the culprit's death, so the punishment is postponed for those who cannot endure it. If it cannot be carried out, it is lifted. Whipping is considered torture and is not legitimate. It was applied to gangs in the early years of the Turkish Republic.

This is the primary form of punishment in schools and everywhere, including the military, all around the world. It is also applied to tradesmen in flagrante delicto. The offender is laid on the ground, their feet are tied to a flat pole called "falaqa," and two people hold this pole on either side.

Depending on the nature of the offense and the culprit's tolerance, a third person strikes the soles of their feet. It causes pain but the individual recovers quickly. In the military, a bugle is sounded during this punishment.

Whatever the Cost, Let's Pay

In some crimes, fines are imposed on the offenders. In cases other than premeditated murder, for instance, in cases of assault, abortion, or injuries, compensation is paid in installments to the heirs of the victim or to the injured person. If the offender cannot pay, they may be forced to work, and the court may also impose additional penalties.

Simple offenses can result in fines. In crimes like counterfeiting, hoarding (black market activities), and corruption, the assets of the offender are confiscated. Excessive wealth observed in the possessions of government officials, trustees of foundations, and guardians is investigated, and if corruption is proven, the assets are confiscated.

Hotel or Prison?

In the history of Islamic jurisprudence, imprisonment is not considered a primary form of punishment. It was seen as contrary to the principle of personal liability and believed to hinder a person from fulfilling their duties to themselves, their religion, their family, and society. Imprisonment often harms the innocent family members, spouse, and children of the offender. The person sentenced to imprisonment may lose their mental health or learn new criminal behaviors.

Imprisonment is a temporary measure used to encourage the offender to perform a specific task, deliver property, pay a debt, disclose an accomplice, or reveal the tools of the crime. Individuals who are considered problematic to mingle with the public, such as sorcerers, fake doctors, and false religious leaders, may be imprisoned. The Zindan Han in Eminönü was the only building used for this purpose in the Ottoman era. (This is now an elegant shopping center with jewelery shops.)

Prisoners are provided with a simple mat to sleep on and enough water and food to sustain themselves without any cost to the state. Their daily religious practices are not disrupted, and they are not allowed to interact with others. However, it is permissible for a wife to stay with her husband for a specific period while he is in prison because imprisonment does not diminish a woman's rights.

Nice to Take Some Distance

In certain cases, it may be necessary to relocate the offender from one city to another for a specified period. The court determines the location, form, and duration of this measure. Exile to foreign lands is not permissible.

In the Ottoman Empire, confinement to a tower (qula-band) or residence in a castle (qala-band) was a form of punishment.

A person under "qalaband" could move around freely during the day, engage in work, but could not leave the castle; they had to report to the castle command at the beginning and end of the day to confirm their presence. On the other hand, someone under "qulaband" could not leave the room they were confined to.

How Many Rowers Are Needed?

To meet the rowing needs of the navy, certain offenders were sentenced to serve as rowers for a specified period. In recent times, rowing convicts were employed in shipyards. The shipyard prisons were referred to as "bagnios." Europeans used the Italian word "bagno," which means "public bath," to refer to North African dungeons.

Both those allocated by the state among prisoners of war captured during wars and those convicted of serious crimes were brought here. During naval expeditions, they would row, and when not at sea, they would work in the shipyards. For security reasons during naval expeditions, only half of the rowers were convicts, and the rest were selected from paid Muslim rowers.

Shipyard prisons also existed in Europe, and their conditions were exceptionally harsh compared to those in Istanbul. After 1785, no prisoners of war were sent to Istanbul's "bagnio." In line with European practices at the time, it was closed in 1863, and a state prison was established in Sultanahmet.

Supplementary Penalties

Except for premeditated murder and involuntary manslaughter, in all murder cases, the offender must pay both diya (blood money) and kaffarah (atonement).

Kaffarah involves freeing a muslim slave; if that is not possible, then fasting for sixty days is required. If fasting is not performed, the court enforces it.

In all cases of manslaughter except involuntary manslaughter, the murderer is deprived of the inheritance of the victim.

Those who are convicted of falsely accusing a chaste woman of adultery (qazf) are not accepted as witnesses until they die. Those who commit serious crimes are also disqualified from giving testimony.

In some crimes, summoning the offender to court, admonishing them with words like "You have committed such a crime!" and offering advice by the judge can serve as an alternative to punishment.

These measures are generally applied in cases of minor offenses and for individuals recognized in society for their good character. Some individuals find the mere summons from a court to their homes to be a torment equivalent to years of imprisonment.

Fictitious Punishments

Exposing individuals such as false witnesses, swindlers, and gamblers for the purpose of deterrence is also a form of punishment. Exposure can take various forms, including publicly shaming the individual, making them ride a horse backwards through the city, or having a town crier announce their crime.

In the Ottoman Empire, those who committed heinous crimes were publicly displayed for deterrence by being "impaled" on a stake, meaning they were tied to a wooden post in public squares.

For the crime of highway robbery, the death penalty was executed publicly, and the offender was exposed for up to three days. It is rumored that until the Tanzimat period (1839), the heads of some executed criminals were displayed on the "Warning Stone" (Turkish: Sang-i Ibrat) in front of Topkapi Palace for a while.

In Islamic-Ottoman law, there were no punishments such as impalement, hanging by hooks, placing someone inside a cannon and firing it, feeding them to wild animals, placing them in a sack and throwing them into the sea, or drowning them at sea.

Some of these narratives are the result of the imagination of foreign travelers. Many of them were written as propaganda tools with the sole purpose of fueling fear and hostility towards Turks and justifying wars to the public, even before some of these travelers set foot in Ottoman territories.

Swiss traveler Jean Baptiste Tallot mentions this issue in his travelogue titled 'Nouveau Voyage fait au Levantes Années 1731 et 1732,' and the famous Romanian historian Jorga touches upon it in his work. Even some serious historians have been misled by these collections of falsehoods and fabrications, which are based on real travel accounts and embellished with fantasies and tales.

Önceki Yazılar

-

NO MARRIAGE WITHOUT PERMISSION!24.07.2024

-

THE TRUTH OF KARBALA17.07.2024

-

CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE TURKS TO ISLAM10.07.2024

-

OUR TRADITION OF THE ENTARI (JALLABIA ) HAS YIELDED TO TIME3.07.2024

-

GALLOPING THROUGH HISTORY: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE'S POSTAL COURIERS26.06.2024

-

SUMMER HAS COME, LET'S GO ON AN EXCURSION...19.06.2024

-

HOW DID THE TURKS LOSE THE ARAB LANDS?12.06.2024

-

IT WAS AN ART OF EXECUTIONER...5.06.2024

-

ARAB NATIONALISM AND THE TURKS29.05.2024

-

HOW DID TURKS BECOME MUSLIM?22.05.2024