.jpg)

A PECULIAR COMMUNITY IN ANATOLIA: PAULICIANS

While Christians were divided into two groups, excommunicating each other—Monophysites and Dyophysites—regarding the nature of Jesus (peace be upon him) in Anatolia in the 8th century, a completely different religious movement emerged: Paulicianism.

Although not widely known, this sect, of exceptional importance in terms of historical influence, saw itself as a universal apostolic church. It rejected the clergy, luxurious lifestyle, the cross, and the divinity of Jesus. This is why it gained popularity among disillusioned masses.

This name was given to them by the Armenians. "Paulician" means "follower of Paul." The intention behind this term is unclear—it could refer to Saint Paul, the Manichaean missionary Paul of Callinicum, or the Bishop Paul of Samosata. Nevertheless, the Paulicians were aligned with the ideas of Paul of Samosata, the Bishop of Antioch in 260.

In Armenian, it's also associated with the meaning of "dirty life," linked to the words "payl" and "keanik." Arabs use variations of this term, such as "Bayalika" or "Beylika."

Oh, Stay Away!

The Paulicians could not document their own history. Information about them mainly comes from their relentless adversaries, Byzantine and Armenian sources, and is often derogatory. They label the Paulicians as a heretical (deviant) group straddling between Christianity and Zoroastrianism.

In 719, Divin (Kars) Armenian Bishop Ohannes, the first to mention them, warns the people: "It is not suitable to host these vile individuals in your homes, talk to them, be neighbors with them, or be friends with them. It is necessary to completely distance oneself from them, to abhor and hate them. For they are the children of Satan. Those who befriend them should be severely punished and kept away from the church."

There have been attempts to connect these with other Christian groups residing in Anatolia. Some of these include the Montanists who lived in Cappadocia in the 2nd century and later went underground, the Adoptionists in the 3rd century who claimed Jesus was merely human, the Messalians in the 4th century who believed salvation was found only in prayer, and the Marcionites who lived in the 7th century. Paul of Samosata was an Adoptionist.

However, there are significant differences alongside the similarities. These groups have, over time, merged into the Paulician community and disappeared. The original Paulicians were the earliest Armenian Christians. The fusion of religion and ethnicity, the convergence of Gregorian Christianity and Armenian identity, took place during the time of Saint Gregory. The Paulicians were excommunicated and separated from the Armenian community. In other words, Armenians became divided into Gregorians and Paulicians. However, as time passed, not every Paulician necessarily meant someone of Armenian descent.

Fifth Column

The sect initially emerged from the conflict between the clergy and the laity; later it gained theoretical attributes. At that time, not only the Paulicians but also communities like the Syriac and Chaldean were under pressure from central religious/political authorities. Having lived in the Byzantine territories where Armenians resided for several centuries, this sect became marginalized due to the oppression.

In Orthodoxy, reverence is given to sacred images known as icons. The iconoclastic (meaning icon-breaking) movement, which claimed that this practice was contrary to the Bible, prevailed in the Byzantine Empire between 726 and 843. This movement provided breathing space for the Paulicians. Emperor Leo III was also a fervent iconoclast.

During this period, the Paulicians even engaged in mercenary service within the Byzantine army. Patriarch Nikephoros even promised the Paulicians freedom if they supported him against the iconoclasts.

However, these days didn't last long. In the early 8th century, when Muslim Arabs penetrated Anatolia, the Paulicians, whom the Byzantines accepted as having the same faith as the Arabs, began to be viewed as a fifth column. As a result, the Paulicians and Arabs started supporting each other in response.

They sided with the Muslims in wars against the Byzantines. In all subsequent Muslim conquests, the support of the Paulicians and their followers was significant. It was not just political gain but also the religious beliefs that contributed to this alliance.

Divriği State

This sect sprouted in the eastern parts of the empire, where political control was loose, such as in today's Eastern Anatolia and Armenia. While it is said to have emerged among impoverished peasants oppressed by feudal lords due to taxes, this explanation is disputable. It originated from religious disagreements among Armenians.

The earliest known Paulician community was seen in the 7th century in Şebinkarahisar (Colonia). Samsatlian Constantinus Silvanus, the first known leader of the Paulicians, established the first church here. They believed that the four Gospels and the letters of Paul were sufficient; there was no need for clerical interpretations.

Simon, who was initially sent by the Byzantine Church for advice, became a disciple and later a successor to this movement. Emperor Justinian II had Simon and his entourage burned alive. Following this, his followers migrated to Tokat.

In Tokat, they faced severe oppression and torture, leading them to establish a militia force. They killed the architect of their torment, the Bishop of Niksar (Neocaesarea), and sought refuge with Umar ibn Abdullah, the Emir of Malatya under the Abbasids. He settled them in Arguvan. Those who faced oppression from all over Anatolia gathered here.

Facing rebellions in the Balkans and the Arab invasion in Asia, the Byzantine Empire, unsure of what to do, sought to establish military garrisons in Anatolia. The Paulicians lived in fortified places, making military operations difficult.

In 750, the Emperor, during his campaign in Armenia, exiled some of the Paulicians to Thrace. Those in the vicinity of Erzincan were exiled to Armenia in 811. In 843, at the order of Empress Theodora, around 100,000 Paulicians were killed.

In response, 5,000 people, led by Karbeas, a former Byzantine officer, revolted and established a state in the fortified area of Divriği. They built castles and defied the empire.

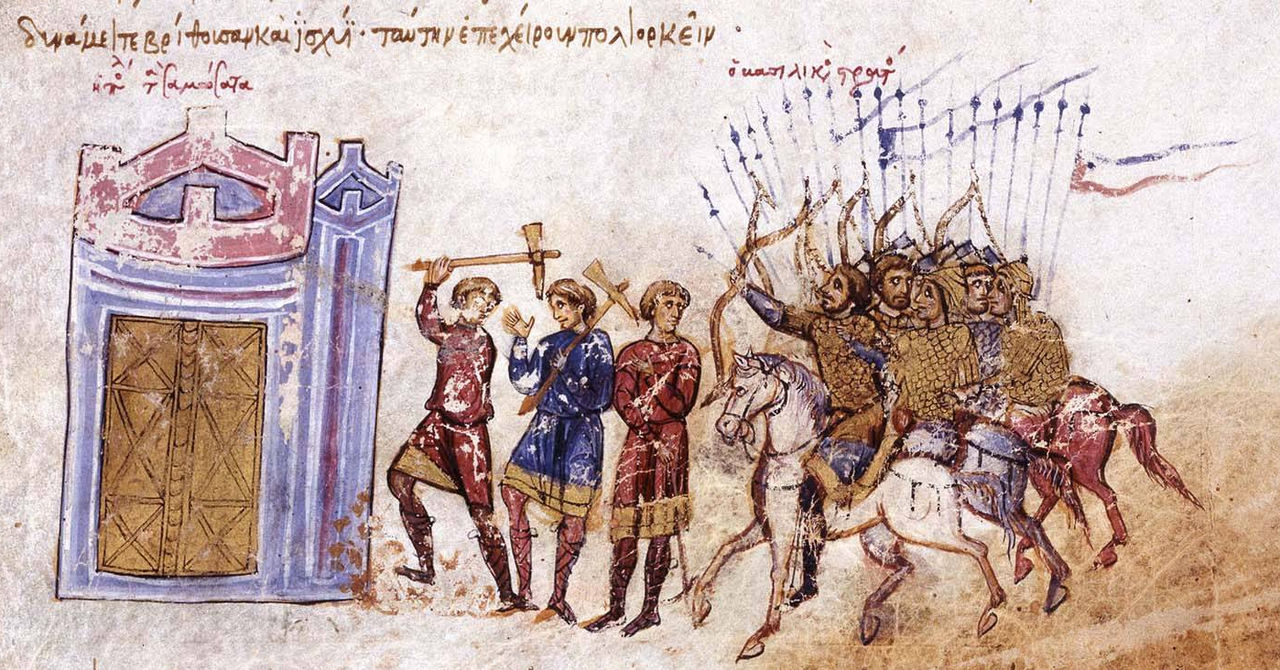

The Paulicians controlled the Divriği-Darende-Malatya line, a strategically important region for both the Arabs and the Byzantines. Emperor Basil I, encouraged by the clergy, took action in 860 to secure the border and resolve the Paulician issue.

"Karbeas inflicted a heavy defeat on the approaching Byzantine army near Tokat. He captured Commander Bardes and hundreds of officers, releasing them in exchange for ransom. He conducted raids on Sinop and Samsun, but he was captured and killed in the Battle of Lalakaon near Ankara when he joined forces with Muslims in 863.

His nephew and son-in-law Chrysocheirus succeeded him and conducted raids on İzmit and Ephesus. Emperor Basil I offered peace in 869, but Chrysocheirus demanded the withdrawal of Byzantium from Eastern Anatolia, preventing a peaceful resolution. In 871, he defeated the Byzantines and captured Ankara. In response, the Emperor launched a full-scale attack on Divriği. Chrysocheirus was killed in 878, leading to the collapse of Paulician resistance.

The weakening of the Abbasids and the dissolution of the Paulicians facilitated Byzantine actions, benefiting the Armenians as well. Armenian King Ashot took advantage of this tension to gain political privileges from both sides, expanding his influence."

Harbingers of Reform

After 873, the surviving Paulicians were exiled to Armenia, Kurdistan, and Thrace. In the first two regions, they assimilated into the local population or lost their influence. However, in the Balkans, where they were settled as a buffer against the Bulgars, they found opportunities to spread, especially among the rural population.

The Paulicians played a crucial role in the Byzantine-Arab struggle in Anatolia, as well as in the Balkans, where they defended the Byzantines against Pecheneg incursions. Those who refused to fight in the Byzantine army were imprisoned with their families in the Paulician stronghold of Philippopolis (modern-day Plovdiv). As a result of the pressures, around 10,000 Paulicians converted to Orthodox Christianity.

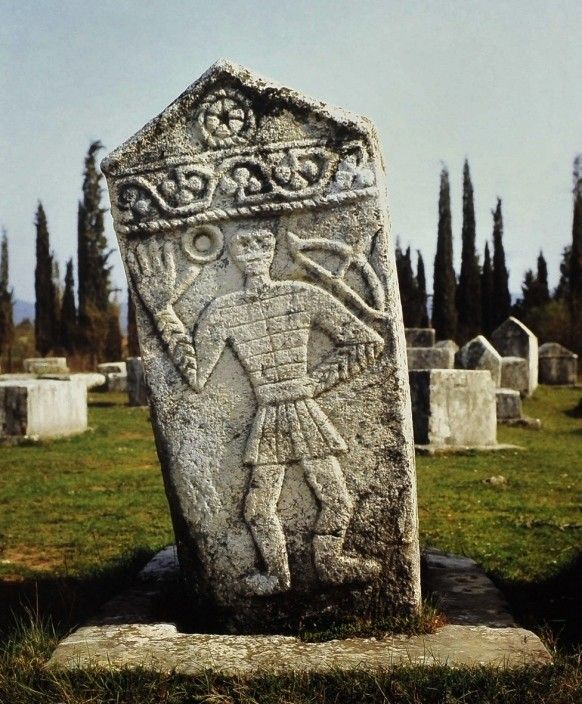

Until the 11th century, they remained relatively out of the spotlight, but this time, they reappeared in the Balkans and Europe under new names. In the Balkans, they were known as Bogomils, in Bosnia as Patarenes, and in France as Cathars and Albigensians. These groups were the successors of the Paulicians.

The Bogomils, who opposed the clergy, and their Bosnian counterpart, the Patarenes, advocated a simple way of life. With their critical, rational, humane, and combative approach, they made significant contributions to the political, social, and intellectual history of Europe.

One of the objectives of the Crusades was to suppress these Bogomils. In fact, many Bogomils living near Philippopolis were massacred by the Crusaders, and their homes were destroyed.

The French counterparts of these groups, the Cathars and Albigensians, faced heavy oppression due to their criticisms of the morally corrupt Church. In the 13th century, many of their members were burned to death. However, their ideas, by generating significant dissent, paved the way for the reform movement.

Bosniaks, Pomaks, Alawites

After the Ottoman Empire's expansion into the Balkans, mass conversion movements in Bosnia and Bulgaria primarily took place among these Bogomils. Bosniaks and Pomaks are a legacy of this period.

The most significant influence of the Paulicians in Turkish culture is the Battal Ghazi Epic. The Arab historian al-Masudi mentions ten heroes who converted to Islam and fought against the Byzantines, two of whom are named Abdallah al-Battal and Omar ibn al-Battal. The Paulicians depicted them in their churches.

The stories told here and in the epic poem about the Byzantine-Arab battles in Digenes Akritas are similar to the Battal Ghazi Epic. According to some, Karbeas is identified with Hussein Ghazi, buried on a hill outside Ankara today, and Chrysocheirus with Battal Ghazi.

Some people, due to the geographic proximity and certain shared beliefs, link the origins of Alevism to the Paulicians. They even associate the Babai uprising during the Seljuk period with the Paulicians.

However, as mentioned earlier, it's quite natural for certain minority communities deemed heretical to share similarities, but this doesn't necessarily imply sameness. This is because due to the severe oppression, massacres, and exile in the 9th century, very few Paulicians remained in Anatolia, and most of them converted to Islam.

Önceki Yazılar

-

"WOE TO THE ENEMIES OF THE REVOLUTION!" What Was The People’s Reaction To The Kemalist Revolutions?2.07.2025

-

DEATH IS CERTAIN, INHERITANCE IS LAWFUL!25.06.2025

-

THE SECRET OF THE OTTOMAN COAT OF ARMS18.06.2025

-

OMAR KHAYYAM: A POET OF WINE OR THE PRIDE OF SCIENCE?11.06.2025

-

CRYPTO JEWS IN TURKEY4.06.2025

-

A FALSE MESSIAH IN ANATOLIA28.05.2025

-

WAS SHAH ISMAIL A TURK?21.05.2025

-

THE COMMON PASSWORD OF MUSLIMS14.05.2025

-

WERE THE OTTOMANS ILLITERATE?7.05.2025

-

OTTOMAN RULE BENEFITED THE HUNGARIANS30.04.2025