WHO ERADICATED THE TEKKES?

In the construction of a well-ordered and healthy Muslim society, along with madrasas (theological schools), tekkes (Sufi lodges) have played a significant role. Turks, upon settling in every city, and even in villages, would first establish a mosque, followed by a madrasa and a tekke, making it their motto to exemplify the beautiful ethics of Islam to everyone.

All of these are waqfs (charitable foundations), and the sheikhs and disciples who operate here are responsible individuals who cultivate fields, harvest crops, raise animals, engage in a trade, sustain the operation of the tekke with their lawful earnings, and provide assistance to the poor.

The famous saying of Imam Malik ibn Anas goes as follows: "One who does not learn fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) and indulges in Sufism (Islamic mysticism) becomes a heretic. One who learns fiqh but lacks knowledge of Sufism becomes misguided. Those who combine both reach the truth." Imam Abu Hanifa and Imam al-Shafi'i, like other leading jurists, jurisprudential pioneers, were also knowledgeable about Sufism.

In the widespread madrasas extending to the villages, Muslims who learned their religion correctly would frequent the nearby tekkes to strive for the internalization of faith. Even beys (local rulers), viziers, and even sultans would kneel before awliya (a spiritually enlightened people) and bow their heads, seeking spiritual guidance. The fundamental principles of the admired Ottoman manners that impress everyone today were built upon the foundation of Sufism and tekkes.

Sufi author Samiha Ayverdi states: "Until the year 1925, there were 365 dargahs (tekke khanqahs) in Istanbul alone. If each of these had at least fifty members, that would make 18,250 people. If each of these individuals had at least five sympathizers among their families, relatives, and surroundings, that would amount to 91,250 people. Considering Istanbul's population was around eight hundred thousand, it means that one-eighth of the city had a spiritual safeguard, like a purification device that serves good rather than evil, setting an example in its vicinity. Thus, the positive and inspiring atmosphere emanating from this strong and reliable mass permeated its surroundings, serving as a zone of safety and trust, preventing the society's bestial and impure tendencies, inhibiting its desires for evil and corruption." (Ne İdik Ne Olduk, 104)

During the Ottoman era, tekkes would monitor each other within the framework of class consciousness, and the government would prevent those who were not qualified from assuming leadership positions in tekkes. In the 17th century, the Qadizadali movement, initiated by a few unrefined and fanatical preachers, resulted in harassment of tekkes and incitement of the public to rebellion. The government's response to this was harsh.

During the reign of Sultan Mahmud II, the Majlis Mashayih (Council of Sufi Sheikhs), which had a degree of autonomy, was established and served as a self-regulating body for tekkes. The members of the Young Turks, on the other hand, attempted to take control of this council in order to manipulate tekkes for their own interests.

The Batiniyya in Tekkes

The forces of the Mongol governor Hulagu destroyed the center of the Batiniyya, Alamut, in 1256, and eradicated their assassins. Those who managed to escape came to Azerbaijan and Anatolia, spreading the new Batini belief under the name of Hurufism among the ignorant population. Over time, they infiltrated first into the Bektashiyyah, and then into other tekkes, including Malamatiyya and Mawlawiyya.

Since Sultan Mahmud II closed the Janissary Corps and the Bektashi lodges due to its connection with it, Bektashi leaders called him the "Infidel Sultan." Sultan exiled these leaders to centers of learning such as Birgi and Hadim as part of his efforts to rectify religious beliefs (tashih al-aqaid). The tekkes were transferred to the Naqshbandi order, which had the closest historical lineage according to waqf law. This event led to animosity among the Bektashis towards the Naqshbandis. During the Young Turks period, they sought revenge in a brutal manner. Prime minister Talaat Pasha, a prominent figure during that time, was himself a Bektashi.

Eradicated Sources of Spiritual Enlightenment

The new regime of Türkiye considered the madrasas, which taught the zahir (exoteric) aspects of religion and protected them, and the tekkes, which nurtured and sustained spirituality, as adversaries; it realized that without eliminating them, the reforms could not be established. After eradicating two important sources of spiritual enlightenment that nourished the society's spirit, the single-party government found it much easier to implement its Westernization program.

On November 30, 1925, with Law No. 677, tekkes, zawiyas (small dervish lodges), and tombs were closed and sealed, and titles related to these and certain other titles were abolished. Tariqas (orders) and Sufi practices were banned, and strict monitoring was imposed on their underground members. Even the imperial tombs were closed and left in ruins. Populism, through the closure of all civil societies, meant that the people had to work solely within the single-party framework.

Sheiks and their families were allowed to reside in the tekkes as long as they were alive and complied with the regulations. However, most of these tekkes were waqf properties, and the principle of waqf law is that no one can alter its terms. Despite this, many of these properties were seized and plundered, and only a few were repurposed as mosque lodgings.

Some tekkes that lost their original essence were later allowed to exist in a folkloric manner. Even government officials would make appearances there on special occasions, while ordinary Muslims were subjected to scrutiny under the accusation of being part of a religious order. Freemasonry, which is a Christian-based order, was allowed to operate freely during president İsmet İnönü's era, while Muslim tekkes remained closed and inactive.

They Closed The Empty Places

The following words of Sayyid Abdulhakim Arvasi, one of the Naqshbandi sheikhs, spoken shortly before the closure of the tekkes , are noteworthy: "For some time, the signs of the Sharia have been hidden, and the main path of the tariqa has been deserted. The infidel ego has invaded everywhere, and the army of Satan is ruling everywhere. The essence of Tasawwuf (Sufism) has been distorted; only its name remains. Its pillars have been shattered, only its form remains. Perhaps even its name and form have undergone changes. Those who are not qualified regard Tasawwuf as gilded, forged money. Yet, Tasawwuf is the mine of truths."

Abdülhakim Efendi, upon arriving in Istanbul in 1919, remarked, that "there seemed to be no tekke left untouched by bid'ah." When the tekkes were closed, he said, "They closed the empty places. Knowledge and tariqa fell into the hands of the ignorant and inexperienced. Tariqa has stopped to exist, but love and companionship remain eternal," thus interpreting the closure of tekkes and madrasas within the framework of divine destiny. Bid'ah refers to innovations introduced into religion and Sufism after their establishment.

So, the firm attachment to the spiritual lineage, achieved through proper practice and observance under the guidance of a qualified spiritual guide (murshid) within a legitimate tekke, to progress through the stages of spiritual journey to attain the special sainthood (wilayat al-hassa) has been eliminated due to political and social reasons. However, the possibility of reaching general sainthood (wilayat al-amma) remains, achieved through correcting one's beliefs, fulfilling obligatory and voluntary acts of worship, engaging in divine remembrance (Dhikr-e-Ilahi), and seeking spiritual nourishment from Allah in a manner that does not necessitate a tekke.

The perfect and accomplished guide (Murshid-e kamil-e mukammal) should possess expertise in ijtihads (legal interpretations), and be at the level of special Muhammadan sainthood (wilayat al-hassa al-Muhammadiyya) within the context of Sufism, enabling them to discern truth from falsehood, and right from wrong. A restricted deputy (muqayyad khalifa), on the other hand, can only be active in the presence of his murshid. They undertake everything under their murshid's supervision and cannot function independently. Even if the murshid is deceased, they are bound to the teachings of him and cannot deviate from them. Even if they have reached a level of perfection (Murshid-e kamil), they are not necessarily a completer of others' perfections (mukammal).

In this period, there is also a symbolic deputy (safir) who is figuratively referred to as "khalifa". They are obedient in all matters related to the order. They are not allowed to express their personal opinions, and only certain tasks like guiding the practice of remembrance (dhikr) or leading Khatme-i Khajegan (a type of dhikr which is performed in jamaat, congregation) can be assigned to them. Many of the tekke sheikhs during the late period of the empire and in the republican era were of this nature.

Where Will Awliya Emerge From?

With their deteriorated state, tekkes were still serving people, aided by deep-rooted traditions, to some extent. People of correct belief and devoted worship were mostly members of a Sufi order. According to what Ahmed Yivlik Baba, the sheikh of the Karabaş Dargah, recounted, Dr. Mazhar Osman, the head physician of Bakırköy mental hospital, says to İsmet İnönü: "Sir, we have run out of space in the hospital. Most of them don't belong here. You closed the tekkes, and you increased the number of patients. At least if you could give us these sheikhs; three-quarters of the patients would recover." İnönü responds, "Neither have you said this, nor have we heard it," and dismisses the matter.

In response to the question, "Sir, tekkes are closed. Where will the awliya emerge from now?" Abdülhakim Arvasi replied, "Those who prostrate their foreheads in prayer now are the awliya of this time." Truly performing prayer (salah, namaz) with sincerity is not within everyone's capability.

Since it's not absolutely necessary to have a tekke for Sufism, in connection with this, Ahmed Celaleddin Dede recited the following lines:

"The dome is the sky, always adorned with the light of stars,

Its brightest lamps are the sun and the moon.

Closing tekkes cannot erase the remembrance of Allah,

All beings remember, the universe is a dargah."

Neither Hindu, Nor Greek!

In the early days, there were no specific places for Sufi activities. Just as education transitioned from mosques to madrasas with the development of Muslim society from various aspects, Sufi activities also began to take place in designated locations.

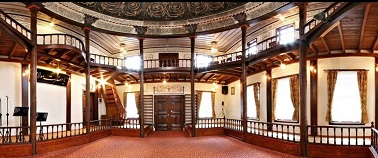

The terms "tekke," "zawiya," "dargah," and "khanqah" have been used interchangeably, but there are distinctions among them. The term "tekke" (or "takiyeh") originates from the Arabic root meaning "to lean against." The equivalent Persian term "dergah" means "a place at the door, entrance." The first tekke was built in the 8th century for Abu Hashim al-Sufi in Ramla.

"Zawiya" comes from Arabic and means "a corner set aside for worship." In a zawiya, there is no sheikh; only dervishes reside, and other members of the order come together at specific times to perform the rituals of the tariqa. "Khanqah," a Persian term, refers to a guesthouse. It is used for the central tekke of the order. Another term for this central place is "asitane," which comes from Persian and means "threshold."

A tekke is led by a sheikh. The sheikh is a person who has been granted the authority to guide others in accordance with the practices of that particular tarikaq by a sheikh in their spiritual lineage that goes back to the Prophet Muhammad. Without this authority, a person cannot guide others or show them the spiritual path. A sheikh may have several disciples to whom they grant the authority to guide others. Among them, one may be active in the central tekke and is known as the postneshin.

Tasawwuf is a discipline that has existed since the time of the Prophet Muhammad. It is not derived from Hindu or Greek philosophy. While there may be similarities between them, Islamic tasawwuf is distinct in terms of its essence and form.

As Shah Waliullah Dehlawi mentioned, there were three types of duties of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him. The first was to convey the commands of the religion to people (tabligh). The second was to enforce these commands when necessary (saltanah). The third was to instill these rulings into the hearts of those who are willing (irshad).

After Prophet Muhammad, each of the rightly-guided caliphs fulfilled these three responsibilities completely. Toward the end of the first 30 years, conflicts and bid'ahs increased. Islam spread across three continents. The light of prophethood gradually faded from the Earth, and the number of Sahaba (companions of the Prophet Muhammad) decreased. It became increasingly challenging for a single individual to carry out all three of these tasks.

These three responsibilities were divided into three categories. The duty of tabligh (conveying the message) was assigned to religious scholars and jurists, known as mujtahids. The responsibility of saltanah (governance) was assumed by the caliphs. As for irshad (guidance), which involves spiritually acquainting willing Muslims with the spiritual aspects of the Quranic decrees, it was entrusted to the great figures of tasawwuf.

Joining a tariqa is not an easy task. Certain conditions must be met for this purpose. A person who fulfills these conditions and is accepted by the spiritual guide (sheikh) is called a "murid" (one who seeks the guidance of the sheikh) or "dervish," which comes from the Persian word "dirigush," meaning "one who turns away from worldly possessions." This term has been adopted into Arabic and other languages as well.

It is not a requirement for the sheikh to reside in the tekke. The sheikh trains the disciples there, attends to their spiritual states, conducts the regular rituals of the tariqa, holds spiritual gatherings (sohbet), and welcomes guests. Since the essence of tasawwuf is dhikr, both group and individual, silent or vocal forms of zikr are fundamental rituals of the tariqa. Sohbet and rabita (remembering the sheikh) also play a crucial role in the development and training of the dervishes.

Tekkes, in all their aspects, serve as centers of etiquette and spiritual refinement. Particularly, the calligraphic plaques hung in the main hall, known as the "diwan hall ," serve as both works of art and instruments of spiritual guidance. One common type of plaque displays the name of the sheikh, which serves as a reminder for those who look at it. As mentioned in a Hadith, "Those who see the men of Allah remember Allah."

Indeed, tekkes often feature calligraphic plaques that carry phrases in line with the culture of tasawwuf, such as "Adab Ya Hu" (O Allah, render us with decency). This is because "No one without good manners can attain nearness to Allah."

The following verse, which teaches the dervishs the value of patience, belongs to Ruhi of Baghdad:

"Behold the ascetic who aspires to become a guide!

Yesterday he arrived at the tekke, today he seeks to become a master!"

Önceki Yazılar

-

MEMORIZATION OF THE QURAN IS AN ANCIENT TRADITION11.03.2026

-

RAMADAN WAS DIFFERENT IN THE ASR AL-SA‘ADAH…4.03.2026

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026