MIGHTY SOVEREIGNS of OTTOMAN THRONE: SULTAN MAHMUD I

Mahmud I was the 24th Ottoman sultan and the 89th Muslim caliph. He was born to Sultan Mustafa II and Saliha Sultan in 1696. After his father was dethroned in 1703, he had a comfortable time as a şehzade (prince) under the guardianship of his uncle Sultan Ahmed III, who ascended to the throne. He received a good education, attending lectures from Ibrahim Efendi, the son of his father’s teacher Sheikh al-Islam Feyzullah Efendi.

His uncle, who was deposed as a result of the Patrona Halil Rebellion that ended the Tulip Era, called on his nephew and advised him, "Do not succumb to your vizier. Always investigate their situation. Don't keep someone as a vizier for 5-10 years. Have mercy. Treat those in need fairly. Treat people in such a way that you don't get their curse. The şehzades are entrusted to you. Don't give up on generosity. Always commit to austerity. Do your deeds yourself; don't trust anyone else. Here, my situation should be sufficient advice for you. My son, this happened to us because your father and I left the state affairs to others. You take charge yourself!” Then the deposed sultan retired to his chamber in the palace, where he died six years later.

Days of chaos

The chief coup plotters were also present at the enthroning ceremony of the 34-year-old new sultan. The putschists, consisting of very low-ranking soldiers, were in power. In order to erase the traces of the former Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Ibrahim Pasha and the memory of the Tulip Era, they wanted the Sadabad district in Istanbul, where hundreds of palaces were built, and Nevşehir, founded by the former grand vizier, to be burned.

The sultan succeeded in saving Nevşehir. He did not consent to the burning of the pavilions in Sadabad but agreed to have them destroyed. Thus, about 120 pavilions in the Sadabad quarter of modern-day Kağıthane district were destroyed.

Patrona Halil, who appointed a Greek butcher who had loaned him meat as the prince of Moldavia (Boğdan), wanted to attend the Divan-i Hümâyûn (Imperial Council) meeting in an unprecedented way. He threw the treasurer and his family out and settled in his mansion. This caused the soldiers who once supported the coup to turn away from the putschists. Grand Vizier Damat Mehmed Pasha, Crimean Khan Kaplan Giray, who was in Istanbul at that time, and Darüssaade (the section of the palace that includes the harem and private chambers of the sultan’s family) chief Beşir Agha supported the sultan.

The sultan invited Patrona Halil, the Albanian-origin mariner, for dinner at the palace. Going to the palace with the hope that he would receive the rank of vizier, Patrona Halil was attacked and killed by executioners. Thus, in line with the unchanging sultanate tradition of the Ottomans, Sultan Mahmud I was able to erase the traces of the coup 46 days later, just like his uncle Sultan Ahmed III had destroyed the coup plotters who orchestrated the Edirne Incident in 1703.

Gangrene

The Iranian wars were ongoing. The Ottoman army claimed a victory near Hamadan, destroying some 30,000 of the 40,000-strong Iranian army. Kermanshah, Urmia and Tabriz were recaptured. Peace was concluded in 1732. Southern Caucasus was given to the Ottomans while Iranians gained southern Azerbaijan.

The commander of the Iranian army, Nader Khan from the Turkish Avşar tribe, dethroned Shah Tahmasp II and replaced him with his 10-month-old son. But the power was entirely in the hands of Nader, who was later proclaimed as the shah. The next year, he besieged Baghdad.

The Former Grand Vizier, governor of Anatolia Topal Osman Pasha, claimed a great victory in front of Baghdad against an Iranian army of 120,000. The Iranian army suffered 30,000 casualties. The wounded shah withdrew. The city, which resisted for seven months, survived the siege. Upon this victory, Sultan Mahmud I was given the title of “ghazi” (veteran and leading Muslim soldier) in 1733.

Nader Shah raided the Ottoman camp in Kirkuk that winter. Topal Osman Pasha, who was already sick, was killed. Then, Nader Shah killed Köprülüzade Abdullah Pasha, the successor of Topal Osman, in Arpaçay. Abdullah Pasha's father, Fazıl Mustafa Pasha, had also been killed 44 years earlier in the Battle of Slankamen during the Austrian wars.

The death of these two acclaimed commanders had destroyed the morale of the Ottoman army. Yerevan, Ganja, Shirvan and Tbilisi were lost. Although the Crimean Khan Kaplan Giray wanted to come to the Ottoman's aid via the Caucasus, the Russians, Iran's ally, prevented this action. Thereupon, the political situation with Russia became tense. The Russians, violating the Prut and Edirne agreements, attacked Azov and Crimea in 1736.

Opportunity

Seeing this turmoil as an opportunity, Austria declared war on the Ottomans the following year. The Ottoman army, which had to fight on two fronts, took back Serbia and Belgrade. Austria sued for peace and the Treaty of Belgrade was concluded in 1739.

Realizing that it could not carry out the war on its own, Russia also sued for peace and an agreement was reached by returning to the status quo antebellum. The Russians were driven out of the Crimea and the Black Sea. The commercial concessions previously given to France, which supported the Ottomans during these events, were renewed.

Nader, who declared himself shah in 1736, regained places conquered during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III and asked for peace by using this advantageous situation. The Ottomans, who were also at war with Russia, agreed. After 13 years of bloody battles, a treaty confirming the provisions of the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab, also called the Treaty of Qasr-e Shirin, was signed in 1736.

Nader Shah, who is considered the last great ruler of Iranian history and wanted to play the role of a warrior like Emir Timur (Tamerlane) in Asia by invading India and Afghanistan, set his sights on Dagestan, Shirvan, Eastern Anatolia and Iraq. In 1743, he crossed the Ottoman border, violating the treaty. Kirkuk fell and Kars was besieged.

Knowing that Nader's strategy was to first deprive the enemy of water, forcing them to surrender, Kars Guard Hacı Ahmed Pasha ensured the flow of water from Kars Stream to the Kars Lake through canals and enlarged the lake even before the Iranian army arrived; he also had ditches dug around the castle. After two months of small-scale but fierce fighting, Nader was forced to lift the siege as winter approached.

In 1746, an agreement was signed in Kerden between Qazvin and Tehran, and the border determined in the 1639 Treaty of Qasr-e Shirin was confirmed. The following year, Nader Shah was assassinated and Iran began to drift into collapse.

A wise ruler

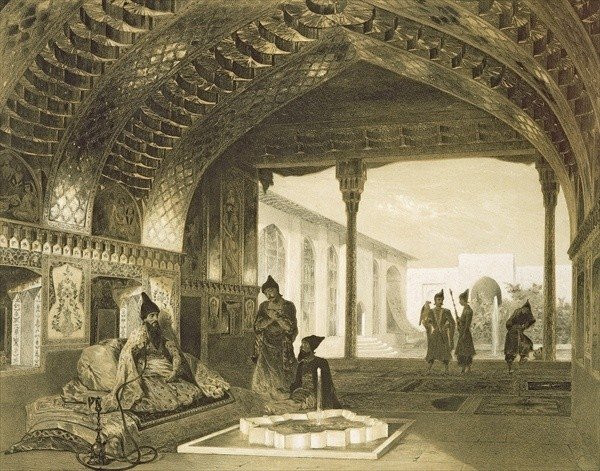

Following these developments, Sultan Mahmud I focused on domestic issues and construction activities. His 35-year reign is considered as being among the brightest days of the Ottoman Empire, similar to a sunny summer day during autumn.

The sultan had built diplomacy on honesty. When King of Austria Karl VI died and his famous daughter, Maria Theresa, took his place, all European states took advantage of the situation and entered the Austrian succession war like crows swarming on carrion. In order to prevent bloodshed, Sultan Mahmud I invited the parties to peace to preserve human rights but his words fell to deaf ears as his counterparts fell below his civil and spiritual level. This noble attitude of the sultan is praised even in some Western sources. Alphonse de Lamartine says that the sultan, who was provoked by France, Russia and Iran to crush Austria, opposed this as a wise ruler.

The sultan used to attend the diwan meetings and listen to the problems of the people. He consulted with those who had knowledge in important matters. The head of eunuchs Beşir Agha, who was also a Naqshbandi sheikh, was one of the closest advisers to the sultan. He served the country immensely without misusing the sultan's favor. Since the agha’s successor with the same name did not bear the same quality, the sultan quickly distanced him from his entourage.

Mahmud I valued the needs and wants of the people and the general sentiment. The sultan knew how to choose his men very well. He would not get attached to them and would dismiss them for the slightest mistake. Instead of removing them completely, he would find another job for them. Mahmud appointed the Anatolian Kazasker (chief judge) Murtaza Efendi, whose chastity and qualifications were known to the sultan, as the kazasker of Rumelia, and later promoted him as the Sheikh al-Islam.

In an imperial edict on the reformation of the Ilmiye (scholars encompassing the ulama) class, Mahmud wrote: "How could those who know and those who do not know be the same?" By writing this verse of the Quran (Surah Az-Zumar: 9), the sultan said that incompetent people should be removed from the Ilmiye class and that the students should be directed to all sciences and disciplines. These anecdotes point to Mahmud’s high level of competence as a statesperson.

The artillery specialist Count Bonneval, who was brought from France for the improvement of the army, converted to Islam and took the name Humbaracı Ahmed Pasha. He established a corps in Üsküdar Ayazma Palace with about 300 bombard and mortar soldiers brought from Bosnia.

He resuscitated the printing press, which was suspended during the coup. A paper factory was established in Yalova.

Handicraft

Like all sultans, Mahmud I had also learned a handicraft in his childhood. After the morning prayer, he used to make seals on precious stones such as agate or collar pins and carvings on stones such as ebony and ivory and sell them in the market. He used to spent what he earned on his personal food items, donating the rest to charity. Lamartine says: “He has not strayed from the advice of the religion that recommends for anyone to live by their own labor.”

The sultan was very religious. He was a follower of the Naqshbandi Sheikh Sayyid Muhammad Muradi in Sufism. He treated scholars well. He invited the great scholar Hadimi from Konya to Istanbul and listened to his lectures. Mahmud’s rejection of the moderate Shiite Nader Shah's proposal to recognize the Imamiyyah Shiism as one of the legitimate interpretations of Islam is evidence of the soundness of his creed.

He was recounted as a good-hearted, mild-mannered, just, dignified, peace-loving, very intelligent and enlightened ruler. After a fire broke out in the Mercan quarter and burned for 12 hours, devastating the local tradespeople, he had the bazaars rebuilt using funds from his own pocket and gave them as gifts to their owners, as proof of his philanthropy. For this reason, his death was mourned by many.

The sultan was fond of flowers. He also enjoyed javelin, horse racing and swimming. He enjoyed watching the moon. He was a master composer; he played the musical instrument tambur. The poems he wrote under the pen name Sebkati show the height of his literary skill.

Bibliophile

Mahmud was famous for his economic policies and filled the treasury with money but he was also very generous in his charitable works. The sultan was a bibliophile. He commissioned libraries in Hagia Sophia, Fatih, Süleymaniye and Galatasaray, as well as in Belgrade and Vidin. He had the precious manuscripts he collected from everywhere put in these libraries. Hagia Sophia alone had 4,000 of the sultan’s books. He established waqfs (charitable foundations) to fund them. The Cağaloğlu Bath, which is still standing today, and the houses he built around it were endowed to the Hagia Sophia Library.

The sultan commissioned a darülhadis (place for studying hadiths) for reading Sahih Al-Bukhari next to the Fatih Mosque and had a primary school built in the Hagia Sophia Complex. State officials also conducted similar activities. Aşir Efendi and Reisülküttab (head clerk, later foreign minister) Mustafa Efendi libraries are from this period. He also built a birdhouse with two floors and six rooms on the wall next to the Fatih Mosque. It seems that the book-loving sultan, known for the libraries he had built, did not forget to take care of birds.

Sultan Mahmud I was known as “mu’ammir-i bilad” (repairer-developer of cities or lands) in his time. He had the official buildings repaired between Istanbul and Edirne. He had repairs and additions made to Topkapı Palace. He created a square by filling in the sea on the Tophane coast. He renovated the shipyard warehouse and the garbage cellar next to it. He had the defterdar (finance minister) building in Sultanahmet’s Çatalçeşme repaired. The sultan also had the Bayıldım Pavilion in Beşiktaş, the Tokat Mansion (Hümayunabad) on Yuşa Hill in Beykoz and the Mihrabad Pavilion in Kanlıca built. The sultan was particularly fond of the Kandilli neighborhood in Istanbul.

Mahmud I had charities outside of Istanbul, too. In Cairo, he had the Sultan Mahmud Lodge and library built, which are still standing and housed Turkish students until recently. He had the Khan Palace, mosque and library repaired in the Crimea’s Bakhchisaray, which was destroyed by the Russians in 1736.

The sultan brought additional waters to the Galata side of Istanbul. The maksem (distribution building) he had built on this occasion is still standing and gave the Taksim district its name (Taksim means dispersal). He distributed the water by having dozens of fountains built in this district. The elegant fountain in Azapkapı was built by the charity of the sultan's mother.

The sultan had the kadem-i şerif (footprint of Prophet Muhammad) brought from the Sacred Relics Chamber of Topkapı Palace, had it placed in an arch with 20 arches made of marble on the qibla side of Eyüp Sultan (Abu Ayyub al-Ansari) Tomb and opened it to the public. He had a soup kitchen built adjacent to Hagia Sophia and attended the opening ceremony in person. At the opening of the library he had built in Galatasaray School, he had the tanks of the fountains built on both sides of the library filled with sherbet and offered it to the public.

Consciousness of duty

On Aug. 13, 1754, Sultan Mahmud I went to the Friday salute even though he was unable to ride a horse. His illness had been going on for two years. He did not listen to the doctors' warnings not to go to the mosque. The people would become restless when the sultan was unable to attend Friday ceremonies. In line with the characteristic feature of the dynasty he belonged to, he made a great sacrifice in order to fulfill both his religious and political duties.

After the prayer, he was put on a horse supported by silahtar agha (the sultan’s aide and commander of his personal guard) as he was unable to walk. Upon entering through the palace gate, he died either of hemorrhoid bleeding or a heart attack in the arms of his entourage. He was 58 years old. He was buried next to his father in the Yeni Mosque (The New Valide Sultan Mosque) tomb in Eminönü.

Sultan Mahmud I had no children, like his brother Sultan Osman III, who later ascended to the throne. No şehzade was born in the palace for 27 years between 1730-1757.

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025

-

WHO BETRAYED PROPHET ISA (JESUS)?26.11.2025