.jpg)

BEING A TRADESMAN NOT AN EASY JOB IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Tradesmen held an important position in Ottoman society. Together with merchants, they formed a central group that led and prevented changes in political and social life

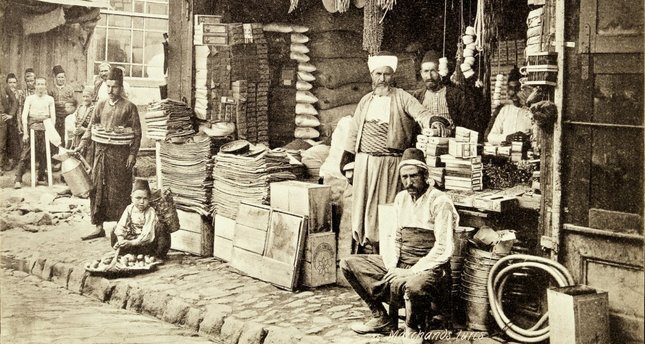

Ottoman tradesmen posing for the camera in front of a grocery store

In the Ottoman Empire as in the Roman Empire, no merchant or craftsman could simply open a shop wherever and whenever they wanted to because a system of controlled economy was employed. That is, to prevent unemployment, cost and scarcity, and thus to ensure social balance in the controlled economy, production was limited in terms of both variety and quantity of goods. The quality of goods produced as well as commercial competition was strictly controlled.

Tradesmen were strictly organized to provide these controls. Thus, they delivered the desired management themselves under the audit of the state and the number of shops or workshops in cities was fixed. No one could open a shop wherever they wanted or do anything other than practices their own trade.

For example, in Istanbul, where 200 shoemakers worked in the middle of the seventeenth century, a new shop could neither be opened nor an existing shop closed, and all existing shops had to remain the same. For example, a shoemaker's shop in the Çemberlitaş district could not be transferred to the Çarşıkapı district without the state's permission. The privilege to trade, issued to craftsmen by the state, was known as the "gedik" (the exclusive license and right to exercise a trade in a particular area). This right could be transferred to someone else either for a fee or free of charge.

License is required

To become a tradesman after finishing elementary school, anyone who wanted to learn a certain craft started out as an apprentice under the guidance of a master. The master taught the intricacies of the art to the apprentice for three years. Then, if the master decided that the apprentice had learned the job to a sufficient standard, he was examined before the elders of the trade union. He was asked questions regarding the religious and commercial ethics involved and was required to make an artifact according to his profession. If he passed the exam, he donned a peshtemal (waist cloth) as part of a special ceremony.

The apprentice who passed the test would continue to work as an assistant master at the same shop, next to his master. He now had the right to open a separate shop, but had to wait for premises to become vacant first. When a shop became available, he would then take over and perform his work as a master in the new shop.

When one of the craftsmen decided to leave his profession, he could transfer his right to exercise his trade to an assistant master from the same union for a fee or free of charge. When the owner of such a right died, his son took over the shop on the grounds of continuing the profession. If he did not have a child or if the child did not pursue his father's occupation, then the right was transferred to an assistant master worthy of his profession. This person was obliged to pay a fee to the heirs of the deceased tradesman. All these transactions were registered in the trades register.

Edebâli was sheikh of tradesmen

Every trade community had an organization established by the masters of that profession. This organization, which resembled the collegiums in ancient Rome, was called a londja (guild) and had been inherited by the Ottomans from the Seljuks. The guild was also a Sufi institution and tradesmen gathered in tekkes or mosques.

At that time, tradespeople called each other "akhi", which means "my brother" in Arabic. After the collapse of the Seljuk state, akhis even established a government in Ankara and played an important role in the selection of the first Ottoman Sultans. Sheikh Edebali, the father-in-law of Osman Ghazi who was the founder of the Ottoman State, was also an akhi and leader of a tannery guild.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, the guilds had lost their Sufi identities after the number of non-Muslims among the tradesmen increased and thus they wanted to establish a separate organization. Under the leadership of the same individual, the establishment was divided into two branches, one for Muslims and another for non-Muslims.

Trade organization

The guild was led by a chief who carried the title of "sheikh", whom the tradesmen chose for life from among the elder masters. According to Evliya Çelebi, there were 105 tradesmen sheikhs in Istanbul.

A "katkhuda" (warden of a trade guild) acted as the liaison between the guild and the government. The tradesmen chose the warden among themselves and referred him to a qadi (judge). If the deemed him an appropriate choice following an investigation, the appointment was made by the government.

Warnings, aids and the rate of profit issued by the government were reported to the tradesmen by the wardens, who also judged whether or not the tradesmen complied with the laws and rate of profit. He also submitted the requests and complaints of the tradesmen to the government. For this reason, the warden needed to be a reputable person in the eyes of both the tradesmen and government. Otherwise, for example, he might pose a risk by overlooking the corruption of the tradesmen.

Tradesmen could report the warden to the if they deemed him corrupt and ask for his deposition, while the government could also depose a corrupt warden.

Father of every profession

The religious and moral principles that all tradesmen had to obey were written in books called "Futuwwatnameh". When a tradesman was about to become a master, he was examined by the principles set forth in these books, which also covered the first person who executed every profession in history. This person was regarded as the peer (patron saint) of the profession. For example, Prophet Idris was regarded as the peer of tailors, while Salman al-Farisi, a friend of Prophet Mohammad, was considered to be the peer of barbers.

Tradesmen who did not comply with the trade ethics or produced non-standard goods were judged and punished, if necessary, before a delegation composed of their guild elders. Tradesmen were also inspected by the and the mayor. If this issue needed to be taken to court, then necessary action was taken. The warden could, if needed, ban a tradesman from his profession for a period of time.

Social security

Tradesmen also had an emergency aid fund under the control of the warden. A tradesman whose shop was burnt, who fell ill or was unable to work, was provided with a interest-free loan, donation and salary from the fund. Every master, assistant master and apprentice paid a fee into this fund in accordance with their income. The fees paid at the tradesmen ceremonies were also deposited there. The goods of the tradesman who died without an heir were automatically left to this fund and the income from the lease of the guild's inventory was also transferred there.

Tradesmen went to the countryside on certain days of the year, ate rice with meat, played games and enjoyed themselves. These festive trips were also attended by the public.

In the liberal economy adopted after the Tanzimat, the guild method weakened. In 1909, the ruling Young Turks removed the guilds in order to break the political and social influence of the tradesmen, as they had more conservative tendencies. Even though trade unions and chambers were established after the Republic, they never reached the power and reputation of the guilds of the past.

Önceki Yazılar

-

HOW THE TURKS SHAPED CIVILIZATION26.02.2025

-

WAS THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A TURKISH STATE?19.02.2025

-

HOW DID THE SUPERPOWERS ACHIEVE THEIR GOAL? THE BACKGROUND OF THE ABOLITION OF THE CALIPHATE12.02.2025

-

FRANCE’S FRIENDSHIP DID NOT BRING PROSPERITY TO THE TURKS5.02.2025

-

PUNISHED TURKISH CITIES29.01.2025

-

WHY AND HOW WAS THE TURKISH REPUBLIC PROCLAIMED?22.01.2025

-

A COMMUNITY IN THE LINE OF FIRE: THE YAZIDIS15.01.2025

-

“WHAT'S THE POINT OF LIVING?” OTTOMAN PRISONERS IN POW CAMPS8.01.2025

-

THE LOST GENERATION OF 1914 - THE BITTER OUTCOME OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR1.01.2025

-

DREAMING OF DAMASCUS AND DELIGHTS...25.12.2024