.jpg)

NEWSPAPERS: AN INTELLECTUAL LEGACY of the OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Newspapers have always played an important part in society, shaping life both socially and politically. A number of newspapers were published in different languages including Arabic, Persian, French, Greek, Armenian and Bulgarian in the Ottoman Empire

Humankind's first encounter with a newspaper took place in ancient Rome. Actia Diurna was a handwritten daily newspaper that mentioned everything from meteor strikes to gladiator fights. There was an imperial newspaper distributed among civil servants in seventh century China. Fogli d'Avisi, which reported on the new developments from the Ottoman-Venice battle front in 1563, was sold for one gazeta, a Venetian coin from the time. Later, the word "gazetta" was used for all daily papers. However, the first daily paper that reported news and announcements like today's dailies was Nieuwe Tijdinghen, a Flemish paper published in the Dutch trade center Anvers in 1603. The British somewhat exaggerated news publishing as there was nearly 300 published daily papers in 1650. Magazines were also published to report on entertainment, art news and political news and the pioneers of newspaper publishers were later followed by France, Germany and the U.S. Reading newspapers became a habit for people and began to shape social and political life as well. Governments refrained from daily papers and imposed pressure on and censored them as much as possible.

Bulletin des Nouvelles, which was published by Istanbul's French ambassador Verniac in 1795, is considered the first daily paper published in the Ottoman Empire. Verniac's first paper was later followed by other papers in French. The newspapers that were published by the French tradesmen during the Greek revolt in 1821 in İzmir unexpectedly supported the Ottoman government.

The first newspaper in Ottoman, "al-Waqayi al-Misriyya," (Affairs of Egypt) was published in 1828 in Egypt. "Taqvim-i Vagai" (Calendar of Facts), which was published by the Ottoman government in 1831, featured official announcements and regulations along with objective local and international news. This paper was also published in Arabic, Persian, French, Greek, Armenian and Bulgarian. The privilege to publish the first private paper in the Ottoman Empire was given to a British man named William Churchill. He distributed "Jarida-i Hawadis," which mainly featured political and financial news in 1840. Following those periods, dailies began to be published in various languages in big cities. To illustrate, 16 newspapers in languages other than Turkish were published in Istanbul while there were two newspapers in Ottoman. The Crimean War (1854-1855) showed the importance of dailies.

Agah Efendi

Agah Efendi

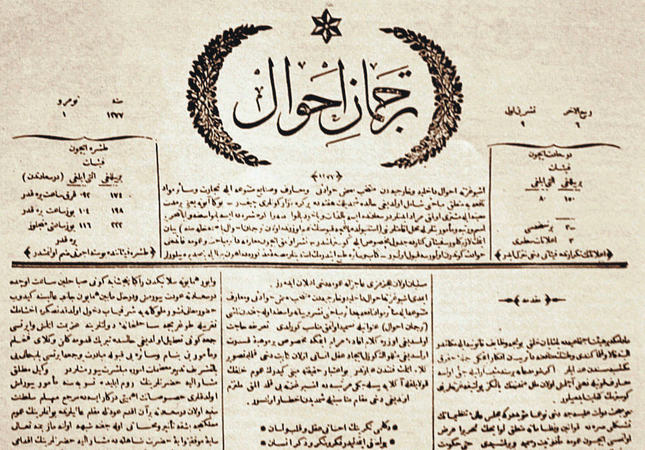

"Tarjuman-i Ahwal," was the first newspaper published by a Muslim named Agah Efendi in 1860. It was distributed two times a week and had a daily circulation of 24,000 copies. The anti-government Young Turks who fled to France and Egypt published dozens of dailies to spread their ideology. The Press Law that entered into force in 1864 declared the freedom of press, similar to European practices. The 12th article of the 1876 constitution declared the freedom of press within the limits of law. However, a censorship commission was formed in 1878 and news deemed immoral or against religion and public welfare was banned. After that, magazines, books and publishing houses were also kept under control.

The censorship commission was formed by virtuous and educated people, but they tightened their control a little bit more and newspapers adopted a careful approach to news publishing. Sometimes these controls led to comical incidents. For instance, they refrained from using the word "yıldız" (star) as it was also the name of the sultan's palace, and the name "Murad," as it was the name of the previous sultan. To avoid ill-minded people's behaviors, political assassinations were published as natural deaths. The lines banned by the censorship commission were printed in white, but the commission later asked the newspapers to prevent such mistakes.

Nevertheless, the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid was a period when many newspapers were published and the number of readers increased. There were a total of 113 newspapers and magazines published in Istanbul between 1867 and 1878. There were newspapers whose circulation was 30,000 in a city with a population of 500,000. Newspapers aimed to inform the public and help people acquire the habit of reading instead of promoting political opposition. The number of episodic novels, poems, cultural articles, comedy pieces and travel pieces also increased. The sultan would want newspapers to be distributed even in villages as he believed it would spread his control over a larger area.

In 1900, the number of foreign newspaper copies in the Ottoman Empire surpassed 100,000. Around 20,000 copies were published in Istanbul by Levantines. In the same year, there were 139 Levantine newspapers and magazines. Ottoman intellectuals read these publications, most of which included unrestricted features as much as possible. Through them, the empire's capital city was kept informed about the world.

Aside from Arabs, non-Muslim Ottoman citizens, including Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Bulgarians, ran their own empire-wide and regional newspapers and magazines. In 1908, 109 out of 726 magazines and newspapers that were allowed to be published were in Greek. From 1908 to 1914, there were 399 Arabic newspapers and magazines. It was difficult to send Istanbul newspapers to Anatolian cities because each city used to publish its own established newspaper.

The day after the declaration of the constitutional monarchy on July 23, 1908, all journalists gathered and rejected the censorship on newspapers and censorship ceased. July 24 is celebrated as Journalists and Publishing Day in Turkey. When censorship was abolished, newspapers began to publish pieces critical of Sultan Abdülhamid and the former regime in both correct and incorrect ways. This practice facilitated the explanation of why the sultan was toppled to the public. In 1908, 353 newspapers and magazines were published in Istanbul. The circulation of "Iqdam," a daily political newspaper, was around 40,000.

However, following the censorship law approved by the Party of Union and Progress (CUP), opposition voices emerged everywhere as the regime of Sultan Abdülhamid was missed. For the first time, differences in political opinion were reflected in newspapers. Hasan Fehmi and Ertuğrul Şakir, two authors for "Serbesti" (Liberty) newspaper, a prominent opposition publication, were shot on Galata Bridge by a pro-CUP group. Fehmi was killed and his funeral attracted thousands who turned out in a show of strength against the CUP. Journalist Ali Kemal, who was later known for his stance against the government in Ankara, encouraged many students at the Faculty of Political Science by saying: "These bullets were fired against freedom of thought." Thousands marched to Bab-ı Ali (the Sublime Porte) to find the murderers. Also attracting public attention, the crowd did not find what they want at Bab-ı Ali or the Turkish Assembly, and instead, the soldiers fired into the crowd.

Istanbul-based newspapers were stayed aloof with the Ankara movement. They retained their stance following the declaration of the founding of the Republic, but the government took its revenge. In 1925, journalists were arrested upon the East Reform Plan. Only two newspapers in Istanbul and one in Ankara were allowed to continue publishing. The president did not intend to travel to Istanbul until that time, but came in 1927 after nine years. From 1908 and 1914, the daily circulation of Istanbul-based newspapers was above 100,000. In 1928, the circulation of Istanbul- and Ankara-based newspapers was 19,700. This amount was lower than those in the Ottoman Empire mostly due to the alphabet reform. The 1931 press law allowed the government to censor publications. Articles including those on religious, nationalist ideas and political criticism were prohibited.

Önceki Yazılar

-

HOW THE TURKS SHAPED CIVILIZATION26.02.2025

-

WAS THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A TURKISH STATE?19.02.2025

-

HOW DID THE SUPERPOWERS ACHIEVE THEIR GOAL? THE BACKGROUND OF THE ABOLITION OF THE CALIPHATE12.02.2025

-

FRANCE’S FRIENDSHIP DID NOT BRING PROSPERITY TO THE TURKS5.02.2025

-

PUNISHED TURKISH CITIES29.01.2025

-

WHY AND HOW WAS THE TURKISH REPUBLIC PROCLAIMED?22.01.2025

-

A COMMUNITY IN THE LINE OF FIRE: THE YAZIDIS15.01.2025

-

“WHAT'S THE POINT OF LIVING?” OTTOMAN PRISONERS IN POW CAMPS8.01.2025

-

THE LOST GENERATION OF 1914 - THE BITTER OUTCOME OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR1.01.2025

-

DREAMING OF DAMASCUS AND DELIGHTS...25.12.2024