"I AM THE GOVERNOR, NOT A BANDIT!" HOW DID THE OTTOMANS CONFRONT THE ARMENIAN ISSUE?

George Clooney's journalist wife, Lebanese Christian Amal Alamuddin, perhaps due to historical ignorance, strongly stated that the Armenian relocation should be addressed on a legal platform. This is a very common and incorrect information. However, the events related to the relocation, which are part of the history of the Young Turks, were subsequently addressed by the Ottoman government, and the legal case was closed.

April 24

Established with the support of Masonic societies worldwide with the goal of dethroning Sultan Abdulhamid II, the Young Turks (the Committee of Union and Progress), which came to power through a military coup in 1908, attempted to eliminate all non-Turkish elements a few years later within the framework of the nation-state project imposed on them. While subduing Greeks and Arabs, they also exiled Armenians and Assyrians in the Ottoman territory to Syria.

Taking courage from the victory at Gallipoli, the deportation was carried out in three stages. Firstly, on April 24, 1915, it was claimed that Armenians, in order to cover up the impact of the Sarikamish Disaster, had attacked the army from behind. The political, religious leaders, and intellectuals of Armenians in Istanbul (235 people) were detained and exiled to Çankırı and Ayaş (two towns in the middle of Anatolia).

Among them were also those opposing the separatist nationalist movement. Similar operations were carried out in towns like Yozgat and Sivas. This was a political suppression operation, aiming to eliminate people with the capacity to make the society's voice heard. They were never heard from again. April 24 has been declared as the day of genocide.

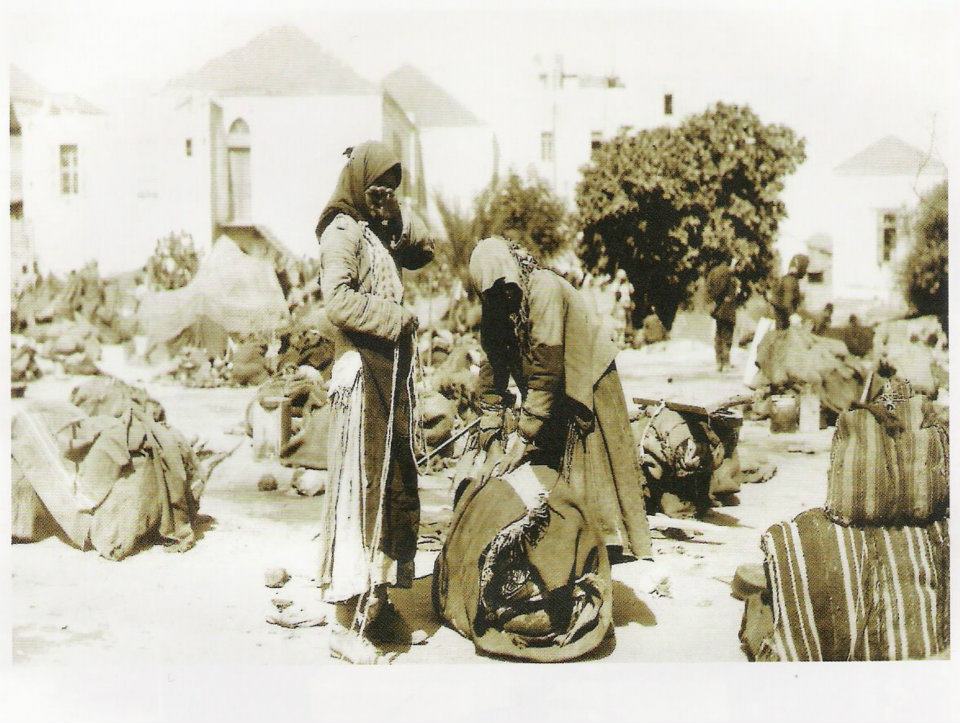

In the second stage, with the law dated May 14, 1915, on the days when the Armenian uprising and Russian occupation began in Van, Armenians in Anatolia and Rumelia were deported to camps in Syria from late spring to autumn. Women, men, families, children, the young, the old, the sick, the healthy – half of the 1 million deportees died from hunger, cold, disease, and bandit attacks.

In the third and final stage, those in the camps were condemned to die from hunger. Resistance in Urfa and Antakya yielded no results. The children of the deportees were placed in orphanages or with Muslim families, while their properties were confiscated. As Anatolia was occupied by the Russians, Armenian gangs in the Russian army tried to take revenge on the Turks living here for the deportation they were subjected to.

The mercy of Superiors

Under the conditions of that time, conducting the transfer of so many people seemed nearly impossible. Moreover, the official orders issued at the beginning of the deportation were filled with detailed measures to ensure the safety of Armenians' lives and properties. The army units transferred from Ulukışla, a small train station town in the middle of Anatolia, to the Caucasian front, consisting of young and strong men, were losing one in every four soldiers due to shortages of food, medicine, and equipment.

Due to the lack of coordination between the central government and local authorities, the fate of the deportees was left to the discretion of local administrators. Some adult men were killed at the beginning of the journey. Some of the young men had already fled to Russia before the deportation.

Only a small number of gendarmes were assigned to ensure the security of the deportees. As a result, some defenseless wayfarers were robbed, killed, and raped by Kurdish and Circassian gangs, deserters, and even local gendarmerie.

Deported groups initially stayed in temporary camps, many of which lacked even tents. After a long journey on foot, they were then sent to camps in Deir ez-Zor and Basra. Since there was famine in the towns reached along the way, the survival of those deported seemed nearly impossible. Even those who reached the camps died due to hunger and disease. Thus, during the deportation, one in every two Armenians lost their lives.

I Am a Governor, Not a Bandit!

Many Ottoman bureaucrats opposed the deportation. Rahmi Bey, the governor of Izmir, using his influential position among the Young Turks, prevented the deportation of Armenians in Izmir. Celal Bey, the governor of Aleppo and later Konya, despite declaring the Young Turk government as a national cause, did not pay attention to the deportation. As a result, he and the district governor of Antep, Şükrü Bey, were dismissed from their positions. The memoirs of Celal Bey are firsthand sources shedding light on the subject.

Ankara Governor Mazhar Bey, who opposed the deportation by saying “I am a governor, not a bandit,” was dismissed in August 1915. The district governor of Kütahya, Faik Ali (Ozansoy) also opposed the deportation and assisted those who were deported to Kütahya. Governors Reşad Bey of Kastamonu, Cemal Bey of Yozgat, and Tahsin Bey of Erzurum were Ottoman bureaucrats who did not implement the orders of extermination.

Malatya Mayor Azizoğlu Mustafa Ağa, who tried to prevent the deportation, was shot and killed by a Young Turk militant under the accusation of “protecting infidels.” Lice kaimakam (provincial district governor) Hüseyin Nesimi Bey, Beşiri deputy kaimakam Sabit Bey, Basra Governor Ferid Bey, Müntefik district governor Bediî Nuri Bey, and journalist İsmail Mestan, who opposed the deportation, were killed under the orders of the Young Turk governor of Diyarbekir, Dr. Reşid Bey.

Mardin district governor Hilmi Bey narrowly escaped death. Savur district governor Sıtkı Bey and Midyat district governor Nuri Bey treated those deported during the deportation well. There were many civilians and Kurdish tribes who assisted the deported. The Committee of Union and Progress's Armenian Refugee Inspector Çerkez Hasan Amca also saved around 25,000 Armenians from death in the camps.

I Didn't Count, Was It More or Less?

On the contrary, military figures such as the Commander of the 3rd Army Mahmud Kamil Pasha, Colonel Seyfi from the military intelligence department, Enver Pasha's uncle Halil Pasha, and brother Nuri Pasha, Commander of the 6th Army in Mosul Ali İhsan (Sabis) Pasha, Deli Halid Pasha, Enver Pasha's henchman Yakub Cemil; Committee of Union and Progress members Bahaddin Şakir, Dr. Nazım, Governor of Diyarbekir Dr. Reşid, Governor of Trabzon (Sopalı Mutasarrıf) Cemal Azmi, Governors of Bitlis, Baghdad, and Mosul Mehmet Memduh, Everek kaimakam and Zor district governor Salih Zeki, Minister of Education Ahmet Şükri, Police Chief İsmail Canbolat, Topal Osman of Giresun, and Yahya Kahya of Trabzon were among the infamous figures associated with the deportation.

Bahattin Şakir, as early as 1914, approached prominent Dashnak figures, with whom he was on good terms at the time, proposing an attack on Russian Armenia, but the Dashnaks rejected the idea. Ali Fuad (Erden), the aide-de-camp of Governor Cemal Pasha of Syria, expressed his excessive admiration for Cemal Pasha on numerous occasions in his memoirs. However, he also admitted that Cemal Pasha supported the bandits who massacred the deported individuals and that those deported were left to die of hunger in concentration camps at his command.

When asked about allegedly causing the deaths of 200,000 Armenians and 50,000 Arabs in Baghdad during World War I, Kut Halil Pasha replied, "They rebelled, and I ordered their extermination. I don't know whether it was less or more because I didn't count." Similarly, when Zor district governor Salih Zeki Bey was questioned in the Ottoman Military Tribunal about the claim that he had caused the death of 10,000 Armenians, he famously responded, "I have honor. I wouldn't stoop to 10,000. Try increasing the number!"

Confronting the Past

After the collapse of the Young Turk dictatorship in 1918, the Ottoman government showed the courage to confront these issues. Armenians were allowed to return to their homeland, and the legislation regarding the liquidation of Armenian properties was repealed. Unlawful events that occurred during the Armenian deportation were brought to court. Investigations were carried out against 1,397 government officials. Even though the Young Turks had destroyed archive documents before fleeing, those found guilty based on living evidence were subjected to various punishments. Forty people were sentenced to death.

Among them were three governors: Kemal, acting district governor of Yozgat and kaimakam of Boğazlıyan, Nusret, district governor of Urfa, and Reşid, governor of Diyarbekir. Even the Yozgat mufti of the time, Hulusi Efendi, testified tearfully against the acting district governor. The first two were hanged. The third, realizing he would be captured, committed suicide. In the Republican era, all of them were declared national martyrs, and the seized Armenian properties were given to their families. Schools and streets were named after them.

When the war was lost, the leaders of the Young Turks who hastily fled abroad were assassinated by the fedayeen of Operation Nemesis, in accordance with the decision taken at the annual congress of the Dashnaksutyun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation). Talat Pasha, sentenced to death in absentia by the Ottoman Military Tribunal, was killed in March 1921 in Berlin; Said Halim Pasha in December 1921 in Rome; Bahaddin Şakir and Trabzon Governor Azmi in April 1922 in Berlin; Cemal Pasha in July 1922 in Tbilisi; and Enver Pasha in August 1922 in Tajikistan. The remaining leaders were exiled to Malta by the British but later released to join the movement in Ankara. Dr. Nazım and Canbolat, characterized by Şevket Süreyya Aydemir, Young Turk sympathizer journalist/historian, as the “chief of the terror wing of the CUP,” were hanged in 1926 due to the Izmir assassination.

Thus, the legal case on the events was closed. However, after the occupation of Istanbul, the Ankara government did not consider the decisions made by the Ottoman government valid. Although established under the pressure of the occupying forces, the Ottoman Military Tribunal worked based on the existing legal system and evidence, and it was through this that permission was granted for the establishment of the new Türkiye.

However, the infiltration of some members of the Young Turks into the newly formed Ankara government and their role in constructing the official ideology complicated the resolution of the issue. The Armenian deportation was turned into a taboo and a red line, leading to difficulties for Türkiye on the international stage.

New Era

The founders of the Ankara movement, in order to appease Western reactions, repeatedly stated that a small committee was responsible for the crimes committed during the Armenian deportation, and they assured that those responsible would be punished, and such a thing would not be repeated. Indeed, Mustafa Kemal's statement to American General Harbord in September 1919 in Sivas and the Amasya Protocols signed with the Istanbul government in October 1919 explicitly addressed this issue.

Although the first three presidents did not have direct involvement in the deportation, the Young Turk bureaucrats and politicians who played a negative role in the deportation were sent to Malta by the British and later sent to Ankara, where they rose to high positions in the new regime. As Ankara gained strength militarily and politically, its stance on this issue gradually changed. In 1919, it began paying a pension to the families of those convicted in the Military Tribunal. The properties seized from Armenians were allocated to these families. However, it did not allow the return of deported Armenians in accordance with the provisions of the Armistice.

Finally, on March 15, 1923, in a speech addressed to a tradesmen's association at the Turkish Hearth in Adana, Mustafa Kemal put an end to the matter by stating, “Armenians have no rights in this fertile land. Your homeland is yours, it is Turkish. This country was Turkish in history, so it is Turkish and will live forever as Turkish.”

The Armenian issue was not brought up by anyone until the 50th year of the relocation. Those living in Türkiye were aware of what happened but preferred silence. It was first raised in the Soviet Union in 1965. However, the West did not show interest in this to avoid offending Türkiye.

When Türkiye's reputation declined due to the 1974 events in Cyprus, these allegations gained attention. A terrorist organization named ASALA carried out assassinations against Turkish diplomats. However, when this organization began to offend Westerners with its assassinations, it lost sympathy. With the help of Mossad, Türkiye eliminated this organization.

The issue turned into a deadlock where the West brings it up every year to poke Türkiye, and Türkiye, not fond of Armenians, tries to defend itself by distributing money to the global Jewish lobby.

Legal Case

While denying or ignoring the pain experienced during this period is undoubtedly wrong, holding an entire nation responsible for it is unjust. Genocide is recognized as a crime after World War II, and legal principles do not apply retroactively. In international law, genocide is considered an individual crime.

In the Treaty of Lausanne, a one-year period was granted for the return and compensation claims of people expelled from Ottoman territory. During this time frame, no one applied for or could apply for compensation and return. Consequently, the social and financial aspects of the issue were closed.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, as the Prime Minister of the Republic of Türkiye, on April 23, 2014, nearly a year before the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, described the events as a "humanly unacceptable incident" using the term “tehjeer” (deportation) in nine languages, including Armenian. He expressed condolences to the grandchildren of those who lost their lives. Emphasizing that Türkiye should approach all kinds of thoughts compatible with the universal values of law with maturity, he stated that he did not want these events to be used as an excuse for hostility against Türkiye. This condolence message, causing surprise in some quarters and eliciting reactions in others, is a notable first in recent history and has been reiterated annually on the anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.

Önceki Yazılar

-

FRIENDS OF ENGLAND ASSOCIATON24.04.2024

-

THE ASIA MINOR CATASTROPHE OF GREEKS17.04.2024

-

HOW DID WOMEN VEIL, AND THEN HOW WERE THEY UNVEILED…10.04.2024

-

HOW CAN HISTORY BE BELIEVED?3.04.2024

-

THE OFFICIAL MADHHAB OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE27.03.2024

-

WHO ORDERED THE PLUNDER OF ISTANBUL?20.03.2024

-

THE PLAYS BANNED BY SULTAN ABDULHAMID IN EUROPE13.03.2024

-

WHAT WAS THE MISTAKE OF THE UMAYYADS?6.03.2024

-

UNRAVELING THE UMAYYAD PERIOD: TRIUMPHS, TRAGEDIES, AND TRUTHS28.02.2024

-

OTTOMAN PENAL CODE AND HOMOSEXUALITY21.02.2024